They topped the second hill, and then the path sloped through a head-high swatch of bush and tangled underbrush. It narrowed and then, just ahead, Louis saw Ellie and Jud go under an arch made of weatherstained boards. Written on these in faded black paint, only just legible, were the words PET SEMATARY.

— Stephen King, Pet Sematary, 1983

King's spelling of cemetery as sematary is intentional—it is a use of realism, which is the practice in writing to accurately represent real life. In this case, we have a young child who has phonetically spelled cemetery, a word for a place set apart for the burial or entombment of the dead, on a sign without a dictionary on hand. In Middle English, the word was spelled cimitery. It is from Anglo-French cimiterie, which, in turn, is from Late Latin cimiterium and coemeterium, and ultimately from Greek koimētērion, meaning "sleeping chamber," and the verb koiman, "to put to sleep." (Considering this orthographic evolution from Greek to Latin to Anglo-French, we can certainly understand the child's misspelling—at least he or she applied phonetics to spell it out.)

The soil of a lexicographer's heart is stonier, Louis.

Before we get too far past sematary's gates, we'd like to mull over its possible utility in different contexts. Hypothetically, it could pass as an adjective form (using the suffix -ary, meaning "of, relating to, or connected with") related to the noun sematology, which refers to the study of word meanings. It could also quite possibly be used as a synonym of sematic, meaning "serving as a warning of danger" and used of the conspicuous colors of poisonous or noxious animals. Both sematology and sematic derive from Greek sēma, meaning "sign."

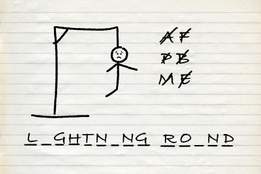

This type of lexical rumination could come in handy as a diversion if you are aghast at the horror that unfolds in King's story, which is about children burying the bodies of pets who get run over on a road in rural Maine in the "sematary," which so happens to be by an ancient burial ground. If it does anything to tamp down the impending terror, we'll look at the word's phonetic substitutions one by one. Slowly. With the lights on.

The replacement of the c with an s can be phonetically rationalized because the letter c when followed by e is sounded \s\, as in cent. The next substitution, the a for e, occurs because in cemetery the middle vowel is pronounced as a schwa, which is represented in our dictionary pronunciation as \ə\.

The sound of the schwa is officially described as a "mid central unrounded vowel." Mid means that the vowel is pronounced with the tongue neither particularly high nor low in the mouth. An example of a high vowel can be found in sheep; a low vowel is found in hat. Central means that the vowel is pronounced with the tongue neither particularly near the front nor the back of the mouth, and unrounded means that the lips are not rounded during pronunciation, as \e\ in set. The schwa sound is found in unstressed or stressed syllables (above has a schwa in both syllables) and is represented orthographically by any of the letters a, e, i, o, u, and y. With that said, the choice of the middle a in sematary becomes a phonetic possibility.

The penultimate sound \er\ (as represented in air) can be spelled with an a (as in dictionary, scary) or an e (berry, confectionery). The child, unfamiliar with cemetery, chose ar, and followed it with y, which often concludes multisyllabic words ending in a long e sound (baby, happy).

Phonetically, the spelling sematary is pretty sound, but it drifts a bit too far from its ancient roots and should be considered taboo in your own writing. Much like the things that go on in those woods.