Wild-goose chase

The origin of the idiom wild-goose chase, meaning "a complicated or lengthy and usually fruitless pursuit or search," has nothing to do with the pursuit of the bird—although we can imagine that chasing after and catching one would have its difficulties. The original wild-goose chase was actually a game in which riders on horseback tried to follow and keep up with a lead rider on whatever course he set. The game's name derives from its resemblance to a flight of geese with a lead goose followed by others in formation.

The Wild-goose chase being started, in which the hindmost Horse is bound to follow the formost, and you having the leading, hold a hard hand of your Horse, and make hym gallop softly at great ease….

— Gervase Markham, A Discource of Horsmanshippe, 1593

Early figurative use of wild-goose chase appears in William Shakespeare's tragedy Romeo and Juliet during a scene in which Romeo and his friend Mercutio banter with each other. Urged by Romeo to keep up the repartee, Mercutio says, "Nay, if our wits run the wild-goose chase, I am done; for thou hast more of the wild goose in one of thy wits ... than I have in my whole five." This is said in response to Romeo's banter, "Swits and spurs, swits and spurs! or I'll cry a match" (swits means switches), which makes the allusion to the equestrian game clear. Mercutio uses wild-goose chase to admit he is not quick-witted enough to keep up with Romeo.

This "follow the leader" metaphor fades with the riding game. When the game became obsolete, people began to mistakenly assume that wild-goose chase referred literally to the futile chasing of the bird, leading to today's "fruitless pursuit" sense.

… led him on egotistical wild goose chases like investigating the validity of President Barack Obama's birth certificate.

— Ed Montini, The Arizona Republic, 23 Aug. 2018

Pig's ear

It appears that in the late 19th century, some beer-swilling Brits got goofy with their drunken rhymes and created pig's ear as rhyming slang for beer.

Cor blimey, luv a duck. There I was, in the rubber dub, enjoying a pint of pig's ear, and some bleeding saucepan lids nipped across the frog and toad and bleeding well 'alf-inched me jam jar. I couldn't believe me mince pies. Had to settle me nerves with a swift Vera Lynn. Oh, sorry what was that? You don't understand Cockney rhyming slang.

— Merle Brown, The Daily Record, 28 Oct. 2000

By the 20th century, pig's ear begins being used as an alternative in the 19th-century idiom "in a pig's eye," which is used to express strong disagreement or to suggest something cannot happen.

Whenever we ask our Tory councillors what is going to happen, we get the answer: "Nobody knows, the decision has not yet been made." With respect, in a pig's ear! This is a site that would cost more to repair than to demolish and no doubt the vultures are circling to provide "prestige housing" despite the fact that already built property in Harborne Village has not and probably will not be taken up by the time such a development could be completed.

— Ruth Hunt, Birmingham Evening Mail, 14 Dec. 2009

It is also in the 20th century that the British expression "to make a pig's ear (out) of (something)" is first heard. Its origin isn't certain, but it implies doing or managing something badly—and it could quite possibly be beer-influenced slang.

… the woman who runs the company in charge of the mission, frankly makes an utter pig's ear of trying to win backing from Congress, her heavy-handed argument, where she effectively tells them Earth is doomed and that it's basically Mars or nothing, proving less than popular.

— Mike Ward, The Express, 8 Nov. 2018

There is a proverb, however, to consider as the source. It goes, "You can’t make a silk purse out of a sow's ear." An older version from satirist Stephen Gosson's 1579 Ephemerides of Phialo is "Seekinge … too make a silke purse of a Sowes eare."

The Exorcist novel writer William Peter Blatty was evidently familiar with it and provides another version of the saying.

"I decided, better I should do it than anyone else," he [William Peter Blatty] told writer Bob McCabe for his 1999 book The Exorcist: Out of the Shadows. "I foolishly thought: I can do a good exorcism. I'll turn this pig's ear into a silk purse. So I did it. It's alright, but it's utterly unnecessary and it changes the character of the piece."

— Adam White, The Telegraph (UK), 31 Oct. 2018

The saying implies the futility of an undertaking. In the end, the silk purse will not be materialized, and a mess of pig's ear remains. But, apparently, the exorcism went "alright."

Fly in the ointment

"Fly in the ointment" is an ancient proverbial expression that can be traced to the Old Testament book of Ecclesiastes: "Dead flies cause the ointment of the apothecary to send forth a stinking savour; so doth a little folly him that is in reputation for wisdom and honour." (Some translations render ointment as perfume or as oil). So, a fly in the ointment is an annoyance that spoils an otherwise pleasant situation, or in the case of the passage above, a person's reputation.

The only fly in the ointment could be scattered showers Wednesday, which could lead to a thunderstorm in the unlucky places.

— The Recorder (Greenfield, Massachusetts), 11 June 2018CSU athletics likes to position its self as a collection of good people doing things the right way. In cutting ties with Eustachy, the university rid itself of the fly in the ointment, but missed an important opportunity to do the right thing by exposing Eustachy as the bully sources inside the program say he is.

— Eric Larsen, The Fort Collins Coloradoan, 27 Feb. 2018

Lay an egg

The expression "lay an egg" means "to fail or blunder especially embarrassingly." It is used especially when there's an audience to witness the fiasco, as in sports or the theater, where it is synonymous with the verbs flop or bomb.

Instead of taking care of business and marching closer to another dominant position in the NFL playoffs, the Patriots laid an egg at Nissan Stadium on Sunday.

— The Providence Journal, 12 Nov. 2018

It's uncertain how the phrase came to mean what it does, but there are a couple of theories about its origin. One is that it comes out of the first World War when "to lay an egg" meant "to drop a bomb"—hence, the figurative "to bomb." (It's interesting to note that in British English a "bomb" is a big success, while in American English it's a major failure.)

Another theory about the origin of "lay an egg" has the phrase developing from the sports term goose egg, which refers to a score of zero—hatched from the idea of an egg resembling that number—as in "the team put up another goose egg on the scoreboard." In the sport of cricket, the term duck egg is used for a zero recorded on the score sheet for the batsman. It's not clear which of these, if either, could have incubated the expression since they both come about around the same time in the 19th century.

Elephant in the room

A large elephant in a room is not a thing that's easily ignored—much like a major problem or issue—but you can intentionally avoid it in some way, as by not mentioning it or walking in the opposite direction (of the elephant or your boss). Avoidance of big things that are obviously known is at the center of "elephant in the room."

For years Italian debt has been the elephant in the room of the common currency area, a giant that has threatened a crisis in an economy that (unlike Greece's) is far too big to bail out.

— The Economist, 27 Oct. 2018

Earliest evidence of the phrase, as it is commonly used today in reference to unaddressed problems, is from the title of Marion H. Typpo and Jill M. Hastings' 1984 book An Elephant in the Living Room: A Leader’s Guide for Helping Children of Alcoholics. The phrase does, however, appear earlier in the 1900s in the context of philosophy and the social sciences to indicate something obvious and incongruous, such as social class struggles, but without the implication that it is ignored or avoided:

Financing schools has become a problem about equal to having an elephant in the living room. It's so big you just can't ignore it.

— The New York Times, 13 Sept. 1857

(Yes, the elephant can enjoy the living room, and other rooms, too.)

Monkey

We're going to monkey around with two monkey phrases. The first is "monkey on one's back," which can refer to a desperate desire for or an addiction to drugs or, broadly, to a persistent or annoying encumbrance or problem.

Despite rehab, medically assisted programs and periods of recovery—even an appearance on an MTV show about addiction—the struggle persisted. "He was finding a lot of success with his business (but) this was a monkey on his back, a demon on his shoulder," said Michelle, who is active in Live4Lali and Hearts of Hope, which educate and offer support for substance users, their families and others.

— Mick Zawislak, The Chicago Daily Herald, 29 Oct. 2018At 0-4, CHS is hoping to get that first win, and relieve itself of the monkey on its back, one that grows heavier each week.

— Grady Tate, The News-Examiner (Connersville, Indiana), 14 Sept. 2018

The drug-addiction sense has been around since at least the 1930s with the broader sense of an annoying problem following by the 1950s.

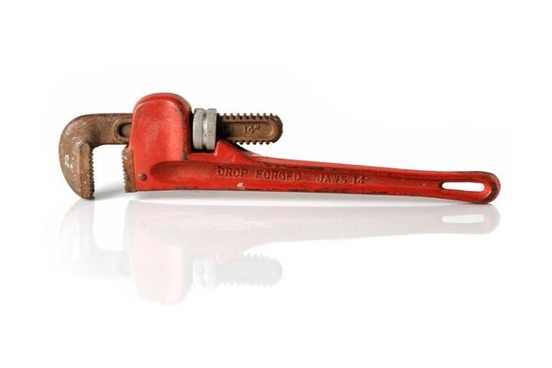

The second is the expression "to throw/hurl/toss a monkey wrench into (the machinery)," which appears in American English in the late 1800s and implies damaging or changing something in a way that ruins it or prevents it from working properly.

It's important to note that plastic or paper with food remnants on it cannot be recycled because those contaminants would throw a monkey wrench into the refining process.

— Matt Murell, The Register-Star (Hudson, New York), 8 Nov. 2018

Monkey wrench is also used outside of the expression with the meaning of "something that disrupts."

Despite some monkey wrenches from Mother Nature, the Cape Fear Fair and Expo saw steady attendance this year….

— The Star-News (Wilmington, North Carolina), 4 Nov. 2018

The name monkey wrench—unlike the mechanical crane, which is named for its resemblance to the bird—appears to have nothing to do with actual monkeys. While it is vaguely possible the tool was named from the slight resemblance of its business end to a monkey's jaws, most popular theories hold that it was named for its inventor.

There are many candidates for the honor of having invented the monkey wrench. One theory suggests a British source, a London Blacksmith named Charles Moncke, but most theorists point instead to inventive Americans, whose names are variously given as Monk, Monck, Monky, Monkey, Monckey, Moncay, Moneke, and Munkey.

The most popular explanation traces monkey wrench to a New England mechanic named Monk who is said to have invented the tool in 1856. The wrench was at first called by another name, but, according to the story, Monk's coworkers soon began calling it a monkey wrench, and the name stuck. This story has been widely told, but no one has yet produced any hard evidence substantiating the existence of the supposed Mr. Monk. The real story about the origin of monkey wrench may never be known.

Mare's nest

A mare is an adult female horse. That said, have you ever heard of a horse building a nest? If you have, you might want to sit down for this story of mare's nest (or of the obsolete synonym horse nest, for that matter). Spoiler alert: there's no such thing. Since the discovery of a mare's nest would be viewed with some skepticism, mare's nest came to be used (with some imagination, we must say) to point out that what someone has discovered can't be true because of its absurdity or ridiculousness; additionally, it is used to indicate that a supposed discovery is actually an illusion or hoax.

You have found a mare's nest. The gentleman you speak of has never been here at all, and the people who bring you news have probably hoaxed you.

— Anthony Trollope, He Knew He Was Right, 1869

The term goes back to at least the 16th century, when Robert Peterson published a translation of the Italian John Della Casa's Galateo in 1576. "Nor Stare in a mans face, as if he had spied a mares nest," he transcribed. (In the passage, he translated Italian maraviglia, meaning "marvel," as "mares nest").

In the 19th century, mare's nest came to be applied to a place, condition, or situation of great disorder or confusion. It is suspected that this use originated as a misunderstanding of the term's original sense; however, it can't be overlooked that illusion and deception do create confusion and sometimes disorder.

Blumenthal makes a determined effort to untangle a mare's nest of conflicting eyewitness accounts, purple journalism, inaccurate police reports, and self-serving statements from relatives and cohorts of Bonnie Parker and Clyde Barrow.

— Kirkus Reviews, 1 June 2018

Kettle of fish

When modified (with irony) by adjectives such as fine, nice, or pretty, kettle of fish refers to a bad state of affairs or a messy situation. On the other hand, when preceded by adjectives like different or another, it carries the meaning of "something to be considered or dealt with." The second sense is much more common today; however, you can still catch use of the "messy" sense from time to time.

Seeing as the whole point of changes this NFL off-season seems to be to try to clear the decks of hated, unfair, counter-intuitive rules, why would the league purposefully dunk itself into another fine kettle of fish?

— John Kryk, The Toronto Sun, 16 Feb. 2018Thermal coffee mugs offer a whole different kettle of fish to regular travel cups. Namely, they keep your coffee hot for hours….

— Tomé Morrissy-Swan, The Telegraph (UK), 14 Nov. 2018

Kettle in the expression doesn't refer to the common vessel used for making tea but to an oblong one large enough to boil a fish, such as the salmon. You have to look inside the kettle to discover how the figurative senses may have boiled up. It seems likely that the kettle's leftover contents—after the fish has been boiled and prepared for serving—led people to associate the mess in the pot to other messy situations in the 1700s. The second sense came about in the next century—perhaps from the need to deal with the mess after dinner (we're conjecturing).

Put the cart before the horse

The idea of "putting the cart before the horse"—that is, in a reverse order—is literally ancient history. The Greeks and Romans had their own versions of this age-old classic; the Romans spoke of "putting the plow before the oxen." The idea appeared in English as early as the 14th century, and within the next two hundred years became the expression we know today, meaning "to do things in the wrong order."

We generally favor using public funds to help reduce inequalities, but creating a special fund—without having actually outlined how it will be spent—is putting the cart before the horse.

— The Baltimore Sun, 29 Oct. 2018

Several, perhaps overly ingenious, explanations exist for the origin of the phrase. According to one, "to put the cart before the horse" did not initially imply attaching the cart at the front rather than at the rear of the horse. Instead, put meant "to arrange as a priority," and the expression denoted the foolhardy act of attending to the vehicle while neglecting the all-important horse.

Another theory holds that the modern use of this phrase refers to the act of reversing the positions of the horse and cart in coal mining in order to prevent the cart from racing out of control. This latter explanation fails to account for the negative connotations of the expression, and, therefore, is not very convincing. More likely, no actual practice was involved, and the idea of expecting a horse to push rather than pull a cart simply struck our ancestors as foolish futility.

Can of worms

The idiom can of worms was unearthed in American English sometime mid-20th century and refers to a complicated situation in which doing something to correct a problem leads to many more unforeseen difficulties. It is considered synonymous with the mythological Pandora's box, which, in English, signifies a prolific source of troubles.

The high court hasn't yet agreed to hear the case. But the lead attorney for the insurer in the case says a ruling favorable to his client would enable the industry to reduce out-of-control, claims-related costs that are driving up insurance premiums…. But his opponent … warns that the court risks opening a can of worms that could drag mortgage companies into untold numbers of insurance disputes.

— Ron Hurtibise, The Orlando Sentinel, 17 Oct. 2018

The idiom is supposedly connected to a literal can containing worms used as bait by an angler—but exactly how is unclear. Did figurative use develop from the opening of a can of worms that was then left unattended allowing the tangle of worms to wriggle out (or at the very least be quite slimy)? That doesn't seem that big of a problem compared to Pandora opening a box (actually, a jar) that released misery and evil over the earth.

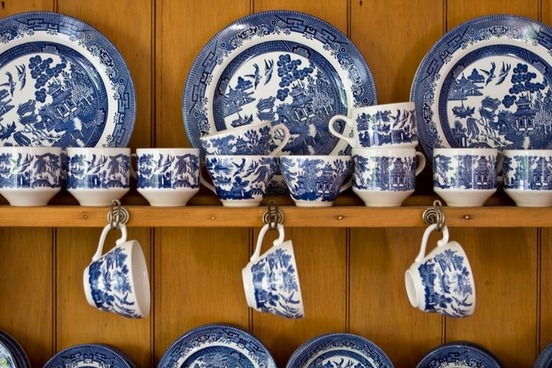

Bull in a china shop

Someone who is said to be "a bull in a china shop" is a person who breaks things or who often makes mistakes or causes damage in situations that require careful thinking or behavior. Although the designation can imply reckless destruction on the part of the said "bull," it often implies clumsiness or heedlessness.

… and if your coat-tail jibes, away goes something, and whatever it is that smashes, Mrs. T. always swears it was the most valuable thing in the room. l'm like a bull in a china-shop.

—Frederick Marryat, Jacob Faithful, 1834Jos, a clumsy and timid horseman, did not look to advantage in the saddle. "Look at him, Amelia dear, driving into the parlour window. Such a bull in a china-shop I never saw."

— William Makepeace Thackeray, Vanity Fair, 1848

Early recorded use of the expression dates to the beginning of the 19th century; however, the epithet is likely older since china shops go back to at least the early 17th century, when the name is first attested in English. Certainly, many delicate wares were clumsily broken by shoppers from the first establishment on, and comparisons of the guilty party to a large animal in the shop struck the minds of at least some of the witnesses—one of those animals being the bovine.

Barnyard Idioms

We will continue to share our favorite animal idioms 'until the cows come home'

SEE THE LIST >