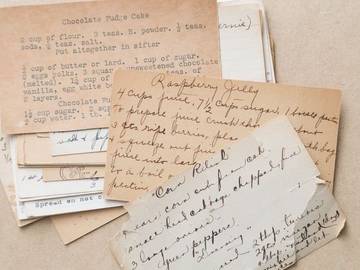

Most of us know the difference between a recipe and a receipt. We think of recipe as the yellowed, typewritten card that your grandmother hands down to you that shows how she made your favorite chocolate chip cookies, and receipt as the 22-foot-long strip of paper and coupons that spits out of the register when you buy a pack of gum at the drug store.

“'Receipt' has a more distinguished ancestry, but since 'recipe' is used by all modern writers on cooking, only the immutables insist on 'receipt.'”

But before we could start, she came shrieking out onto the narrow sidewalk, with a scrawled piece of wrapping paper in her hand, a receipt for what I had paid her.

— M.F.K, Fisher, The Gastronomical Me, 1943

Recipes are basically instructions; receipts are a record of what has been received as part of a transaction. Both recipe and receipt derive from recipere, the Latin verb meaning "to receive or take," with receipt adding a detour through Old North French and Middle English.

But there was a time when receipt was used for what we now call a recipe.

My grandmother used to make a delicious cake that was dense and very yellow. It had a wonderful crunchy, buttery topping that must have been made with granulated sugar and butter, crumbled together. There were no flavorings, except perhaps a little vanilla. We went through all her recipes (she called them "receipts," in the old-fashioned way!) after she passed away but could never find this one.

— Barbara Boissonnas, Cook’s Country, June 1995

The onetime preference for receipt could partly have been influenced by writers who commented on manners, such as Emily Post. Post’s Etiquette, first published in 1922, included a section on “social usage” and said of the two words, “Receipt has a more distinguished ancestry, but since recipe is used by all modern writers on cooking, only the immutables insist on receipt.”

Post, however, had a fondness for receipt herself, describing it as a word of fashionable descent, while recipe, she said, had more of a “commercial” air.

Receipt is the older word, turning up in Chaucer's Canterbury Tales, where it referred to a medicinal preparation (“Whan þat this preest shoolde Maken assay..Of this receit farwel it wolde nat be”). That meaning retained a presence into the 20th century:

Will Beagle said it had a stone some places, and if you put that stone on where a snake or wolf bit you, the stone would draw the poison out. All you had to do when it stopped drawing, was turn the stone around to some fresh place. He believed he could find such a stone in the woods around here if it was daylight. But Sayward said she would stick to her own receipt.

— Conrad Richter, The Atlantic, January 1946

The form recipe is the Latin imperative, and its original use, a couple hundred years after receipt, was not in cooking instructions but in prescriptions, where it was used to preface a list of medicines to be combined (as though to say, “take these”). Eventually that word got abbreviated to an R with a line though the leg, which we later would render in print as Rx. So on a doctor’s prescription pad, Rx originally indicated the command to take that which was listed after, and Rx (or the R with a line through the leg) eventually came to serve as the universal symbol for a pharmacy or pharmacist.

The sense of receipt that we know today—that of a statement documenting the receiving of money or goods—began in the 16th century, and by the 17th century, both words were referring to cooking instructions. While recipe is the preferred word for that meaning today, the memory of being handed down “a receipt for cookies” does get handed down—like a beloved recipe—from older generations:

... And delicacies, such as “graham gems” and boiled cider applesauce, straight out of Grammie Bowles' blue receipt file

— Holiday, November/December 1973I was after a recipe (or "receipt," as my mother called them) for corn bread that came from the heart of the Old South.

— Theron Raines, Gourmet, May 1988I read her letters and her receipt book (receipt is a low country variant of recipe) looking for the small details of life that might show how her days passed, whom she loved and whom she disliked, and what she thought about religion, politics, and slavery.

— Anne Sinkler Whaley LeClercq, An Antebellum Plantation Household, 1996Her receipts, as she insists on calling them (rightly, too), are in the best tradition of New England cooking, often rich perhaps in eggs and cream, but not exotic...

— The New York Herald Tribune Books, 13 Dec. 1942

We recommend folding this new fact into your dinner party repertoire until just combined, then telling over a glass of wine until your friends are impressed.