One of the many words that English has for mocking someone is pillory (“to expose to public contempt, ridicule, or scorn”), a word which, perhaps due to its slightly whimsical sound and orthographic similarity to pillow, seems as though it could have once been something more pleasant. It was not.

The pillory was still used as a punishment for perjury in Great Britain until 1837.

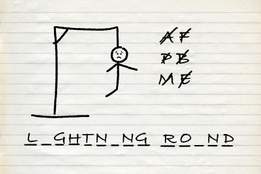

The pillory (plural form pillories) was a device of punishment, ingenious in its simplistic cruelty: “a device formerly used for publicly punishing offenders consisting of a wooden frame with holes in which the head and hands can be locked.” The punishment of getting stuck in a pillory appears to have been rather common long ago, and meted out for offenses that we would today consider minor.

And if he commit perjury, to the damage of his creditors, to the value of 10l., being convicted, he shall be pilloried, and lose one of his ears.

— John Comyns, _A Digest of the Laws of England, 1800

The word, which came to our language from Anglo-French, debuted in the 13th century as a noun, but did not see use as a verb until the end of the 16th century (possibly because everyone was too busy getting pilloried).

The Parliament returned them to our Vniuersitie, who declared them to be schisamaticall, and by a decree bearing date the 19. of May 1408, it was ordeyned that his Bulles should be publikely defaced, also that the Archdeacon with them hanged about his necke, should make an honourable amends, which done hee should be drawne vpon an hurdle to the halles where he should bee pilloried.

— Etienne Pasquier (trans. by Edward Aggas), The Jesuite Displayed, 1594

While there is occasional figurative use of pillory meaning “resembling a person in a pillory” (Robert Southey, in his 1797 Letters Written During a Short Residence in Spain and Portugal, wrote of a man whose neck was “pilloried in his neckcloth”), such use is fairly rare. The far more common extended meaning of pillory is the one dealing with abuse and scorn. This sense started fairly early, about a century after the word began being used as a verb.

Hold, Sir, why so fast? Should your Worship now be found scampering again, and upon the Wing, (though not I hope for Holland) for all your Pilloring of me, you may chance pass with some People for a Knight of the Post too.

— Robert L’Estrange, A Dialogue Between Sir R.L. Knight, and T..D., 1689And since he has further declared, that it was in his Intention a perjury; He has Pillouried himself in Print, as long as that Book shall last.

— William King, A Short Account of Dr. Bentley’s Humanity and Justice, 1699Leuconomus (beneath well-sounding Greek

I slur a name a poet must not speak)

Stood pilloried on infamy’s high stage,

And bore the pelting score of half an age.

— William Cowper, Poems, 1782

When encountered today pillory is almost always used in this “mocking” sense, about which we ought be quite glad.

Closer to home, the Orange County Board of Supervisors, stunned by the county’s bankruptcy and pilloried by constituents, has agreed to make it leaner, more responsive to residents and cheaper.

— The Los Angeles Times, 19 Dec. 1994The Affordable Care Act, pilloried by conservatives as government overreach, didn't go far enough, in Manning's opinion.

— Jenna Portnoy, The Washington Post, 29 Jan. 2018

Why should we be glad that this sense of the word is used? Because, although we tend to think of this punishment as representative of the Middle Ages, it existed well into the modern era. The Oxford English Dictionary, in one of its rare non-lexicographic asides, points out that the pillory was still used in Great Britain until 1837 (but only for perjury; for other offenses it had been abolished in 1815). In Delaware, in the United States, the pillory existed until 1905. So when we consider the alternatives, the figurative use of a mocking and scornful word sounds pretty good.