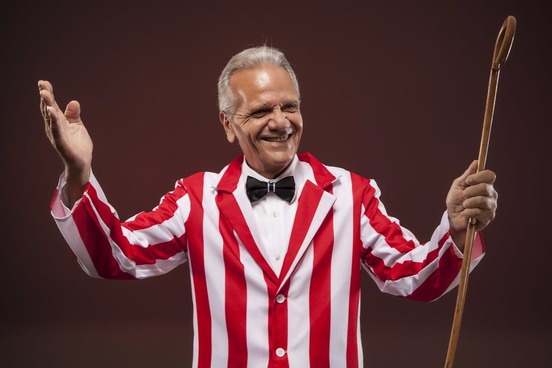

Ballyhoo

Step right up and listen here! Ballyhoo is slang for the attention-getting talk or performance by a circus or carnival barker that is intended to lure passersby to a show.

He'd worked himself up a stunt of sticking a trick knife through one arm to attract a crowd and then starting his ballyhoo ...

— Fred Gipson, Fabulous Empire, 1946

This sense of ballyhoo is first recorded in print in the beginning of the 20th century and, soon after, was extended to exaggerated or sensational promotion or publicity of any kind.

Can Cooney take a punch? Can he go the distance? They wonder. They say he has never been tested, and about this they are probably right. Naturally, Gerry has snappy counters to their jabs. ... But mostly he is wry of the whole prefight ballyhoo.

— William Plummer, People, 14 June 1982

Humbug

Charles Dickens made the expression "Bah, humbug!" famous in the 1843 novel A Christmas Carol, but humbug dates back to the mid-1700s. Even then, however, the origin was unclear: as Oxford and Cambridge monthly The Student stated, "this Humbug is neither an English word, nor a derivative from any other language. It is indeed a blackguard sound…."

What can be said of humbug with confidence is that it has been associated with nonsense and practical jokes. It implies foolishness and trickery and was first used in that regard as both a noun and a verb.

The Surgeon, by Way of Humbug, perswaded the poor Fellow that he really was Pox’d, and prescribed for him: This so effected his Spirits, that he took an Opportunity to go on board the Ship, where there were only two Boys, and hang’d himself up.

—The Ladies Magazine, 11 Jan. 1752

Crocodile tears

The expression crocodile tears is used to describe a display of superficial or false sorrow or anguish about something that we don't really care about. The saying derives from a medieval belief that crocodiles shed tears of sadness while they kill and consume their prey. (We know this to be a crock.)

As the olde Prouerbe: Crocodili lachrymae., the false traiterouse teares of the hypocriticall Crocodyll. Fie therefore and owte vpon theis your Crocodile teares, whereby you wolde perswade & make the worlde beleave, that you wolde redeame and save her honour withe your perpetuall banissement.

—John Leslie, A Defence of the Honour of the Right Highe, Mightye, and Noble Princesse Marie Quene of Scotlande, 1569

Centuries later, people are still accused of shedding "crocodile tears" whenever their expressed sorrow or concern is suspected to be hypocritical.

Furphy

Like scuttlebutt, furphy originated as a word for gossip around the "water-cooler."

The word dates to the early-20th century when a furphy was known in Australia to be a water-cart made by the firm [John] Furphy & Sons. During World War I, various rumors were supposedly brought into military camps by the drivers of the carts, so in time, soldiers began associating the name Furphy with the gossip.

To cheer us then a "furphy" passed around … "They're fighting now on Achi Baba's mound." [Note] Furphy, slang for rumour. In Egypt the various rumours were brought into the camps by the drivers of the water carts. As these water carts were branded Furphy, it is easy to see the origin of the slang meaning.

— Richard Graves, On Gallipoli, 1915

Snow job

Another cool term, snow job, possibly stems from the metaphoric image of being snowed under, but with words specifically. The term snow job refers to the act of persuading or deceiving someone by overwhelming them with information or flattery.

… of the many techniques used to impart credibility, the one that comes most naturally to a journalist such as Mr. Collins is what might be called the Frederick Forsyth Snow Job: blind the reader with a blizzard of facts so that he hardly notices the fiction.

— Ken Follett, The New York Times Book Review, 16 June 1985He really believes in what he's talking about. You feel like you're not getting a snow job. When he talks, he makes you believe that you can win.

— Craig Berube, quoted in Hockey Digest, February 1995

Gammon

British gastronomes will recognize gammon as a word for "ham" or "bacon," and backgammon players know it as a very bad way to lose. But while you were reading about those, another form of gammon was helping to steal your wallet. This gammon refers to deceptive talk, stemming from 18th-century criminal slang where it was used as the nickname for a thief's accomplice who distracts a victim during a robbery.

Hold your peace, and don't bother our game with your gammon, or I will make you as mute as your bedfellow.

— Sir Walter Scott, "The Surgeon's Daughter," 1827

The exact origins of the word are elusive, but it may be derived either from a pun on the game of backgammon, implying the victim is being "played," or from the verb gammon, meaning "to fasten (a bowsprit) to the stem of a ship," playing on the notion of the victim being "tied up."

Sham

Sham can be either a noun or a verb referring to tricks that delude or disappoint. It's believed to be connected to shame, but the fate of that "e" is a mystery lost to the 17th century. Perhaps it comes from the shame felt by the dupe?

What does she make a sham for, and pretend to give me money, and take it away again?

— Charles Dickens, Bleak House, 1853Even Bond could see that Vida was shamming as she lay on the ground, apparently winded.

— Ian Fleming, From Russia with Love, 1957

Cog

Cog, meaning "the tooth on a wheel or gear" or "a subordinate person or part" (as in "He is merely a cog in the machine"), is of Scandinavian origin and rolled into English in the 13th century. Three centuries later, another cog appeared on the scene to denote cheating at a dice game by some sleight of hand (such as controlling the fall of a die or switching a false die for the one in play).

William Shakespeare used it as an undisguised synonym of deceive and cheat as well as a word for the act of getting something by flattery or cajolery.

Scambling, outfacing, fashion-monging boys, / That lie and cog and flout, deprave and slander …

— William Shakespeare, Much Ado About Nothing, 1600Mistress Ford, I cannot cog, I cannot prate, / Mistress Ford. Now shall I sin in my wish; I would thy / husband were dead; I'll speak it before the best lord, I would make thee my lady.

— William Shakespeare, Merry Wives of Windsor, 1602

Put-on

To our knowledge, put-on, meaning "deception" or "subterfuge," is a 20th-century coinage, and a century later the put-on isn't getting old.

I'm surprised by the concerned tone of her voice. Then again, she's so good at faking everything else, even her concern's probably a put-on.

— Tomas Mournian, Hidden, 2011

The name for the ruse is from an adjectival sense that goes back to the 17th century, believed to have evolved from the act of putting on a costume or disguise.

"Will you accept a violet, sir?" said Proserpine, O, how meekly! and curtesying with well-put-on solemnity.

— J. Cypress, Jr., Sporting Scenes, 1842

Obscure Words for Thieves

Featuring 'yeggs', 'jackrollers', 'footpads', and more

SEE THE LIST >