Pandemic

Sometimes a single word defines an era, and it’s fitting that in this exceptional—and exceptionally difficult—year, a single word came immediately to the fore as we examined the data that determines what our Word of the Year will be.

Based upon a statistical analysis of words that are looked up in extremely high numbers in our online dictionary while also showing a significant year-over-year increase in traffic, Merriam-Webster’s Word of the Year for 2020 is pandemic.

The first big spike in dictionary lookups for pandemic took place on February 3rd, the same day that the first COVID-19 patient in the U.S. was released from a Seattle hospital. That day, pandemic was looked up 1,621% more than it had been a year previous, but close inspection of the dictionary data shows that searches for the word had begun to tick up consistently starting on January 20th, the date of the first positive case in the U.S.

People were clearly paying attention to the news and to early descriptions of the nature of this disease. That initial February spike in lookups didn’t fall off—it grew. By early March, the word was being looked up an average of 4,000% over 2019 levels. As news coverage continued, alarm among the public was rising.

On March 11th, the World Health Organization officially declared “that COVID-19 can be characterized as a pandemic,” and this is the day that pandemic saw the single largest spike in dictionary traffic in 2020, showing an increase of 115,806% over lookups on that day in 2019. What is most striking about this word is that it has remained high in our lookups ever since, staying near the top of our word list for the past ten months—even as searches for other related terms, such as coronavirus and COVID-19, have waned.

Pandemic is defined as:

an outbreak of a disease that occurs over a wide geographic area (such as multiple countries or continents) and typically affects a significant proportion of the population

The Greek roots of this word tell a clear story: pan means “all” or “every,” and dēmos means “people”; its literal meaning is “of all the people.” The related word epidemic comes from roots that mean “on or upon the people.” The two words are used in ways that overlap, but in general usage a pandemic is an epidemic that has escalated to affect a large area and population.

The dēmos of these words is also the etymological root of democracy.

This has been a year unlike any other (the word unprecedented also had a significant spike in March), and pandemic is the word that has connected the worldwide medical emergency to the political response and to our personal experience of it all.

Coronavirus

Rarely has a word moved from the jargon of medical professionals to the general public’s everyday vocabulary as quickly as coronavirus. Though not a new word, coronavirus rocketed from obscurity to ubiquity in a span of a few weeks.

The word was largely ignored as the year began, but that changed on January 20th, with the announcement of the first U.S. case of COVID-19. The largest spike in lookups came on March 19th; overall, coronavirus was looked up a staggering 162,551% more this year than in 2019.

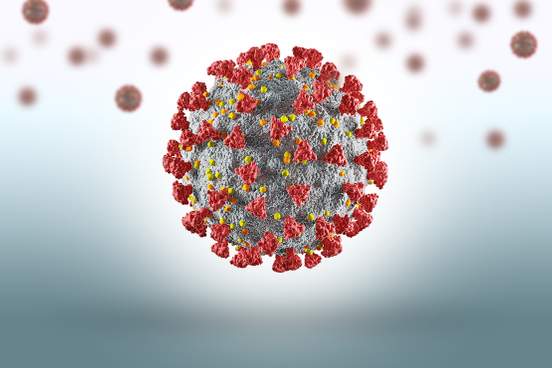

A coronavirus is an RNA virus that was given its name in 1968 by a group of research virologists who noticed that, under a microscope, the virus resembled a solar corona visible during an eclipse (corona is the Latin word for “crown”). Both SARS and MERS are examples of coronaviruses.

The current pandemic is caused by a new, or novel, type of coronavirus dubbed COVID-19 in February. The name stands for “coronavirus disease 2019,” and was added to our dictionary in a special release of new words in March, giving COVID-19 the distinction of being the fastest term to go from coinage to inclusion in a Merriam-Webster dictionary—the process took only 34 days.

Protests in response to the killing of Black people by police officers punctuated the year, and a word from those protests rose in lookups beginning in June: defund. The word was key in the many conversations about how to address police violence, as activists called for the defunding of police forces, and others tried to understand what that in practicality would mean. Overall, defund was looked up 6,059% more in 2020 than in 2019.

We define defund as “to withdraw funding from.” The word is a recent addition to English, in use only since the middle of the 20th century.

In January, the world lost one of basketball’s greats: Kobe Bryant, along with nine other people including one of Bryant’s daughters, died in a helicopter crash. As news of the crash spread, dictionary users searched for a word strongly associated with the player: mamba. “Black Mamba,” he was called—a nickname the player had chosen for himself more than a decade before.

Mamba refers to “any of several chiefly arboreal venomous green or black elapid snakes (genus Dendroaspis) of sub-Saharan Africa,” and comes from the Zulu word imamba. The black mamba in particular is very fast, and very deadly.

Mamba spiked in lookups on the day of Bryant’s tragic death, with users looking up the word 42,750% more than is typical; the next day that number had increased to 66,366%. Overall, mamba was looked up 934% more frequently in 2020 than it had been in 2019.

On July 23rd, Seattle’s brand-new National Hockey League franchise chose “Kraken” as its team name, hurling the word kraken into top lookup territory. Searches for the word increased 128,000% that day.

A kraken is a mythical Scandinavian sea monster; the word, which comes from Norwegian dialect, has been used in English since the middle of the 18th century. Krakens have featured in various contexts more familiar to English speakers than Scandinavian folklore, including various iterations of krakens in Marvel comics and a memorable monster in “Clash of the Titans.” In the 2010 remake of that movie, Zeus commands his underlings to “Release the Kraken” in a particularly dramatic scene. That phrase has gone on to enjoy a life of its own, with “Release the Kraken” being attached to memes as occasions warrant. Kraken spiked in lookups again in mid-November, when lawyer Sidney Powell said she would “release the Kraken,” which in this case meant to present evidence that votes for President Donald Trump had been deleted. No evidence has been put forth, and the Department of Homeland Security has described the 2020 presidential election as “the most secure in American history.”

Quarantine

As the reality of the global pandemic set in, policy responses received as much attention as medical analyses of this new disease. Accordingly, the biggest increase in lookups for one of the most important terms in this new circumstance, quarantine, was on March 20th, nine days after the greatest spike for pandemic.

Quarantine means “a state of enforced isolation designed to prevent the spread of disease.” It came into English through the intersection of French and Italian influences; the French word quarantaine (“about forty”) was borrowed in the late 1400s with a meaning of “a period of forty days”; it later blended with the Italian word quarantena, meaning “isolation of a ship to protect the port city from potential disease.” The Italian term was first used during the pandemic of bubonic plague in the 14th century.

Quarantine is also used as a verb in English, a use that dates back to the early 19th century.

As with pandemic, there was interest in this word before the stay-at-home orders became a reality in the U.S., with February’s reports of outbreaks on cruise ships in early February in the news triggering lookups. Quarantine was looked up 1,856% more frequently in 2020 than in 2019.

The word antebellum was looked up in significantly higher numbers for two distinct reasons in 2020. The first jump in lookups came in June, when an award-winning musical trio announced a name change: “Lady Antebellum” would now officially be called “Lady A.” The second increase came with the September release of a movie that uses the word as its title. These two events made for a year-over-year increase in lookups of 885%.

Antebellum comes from Latin ante bellum, meaning “before the war.” We define the English word in a two-part definition: the word can mean simply “existing before a war,” but it is especially used to specifically mean “existing before the American Civil War.” The enslavement of Black Americans that so painfully characterizes the antebellum period was centered in both instances of the word’s increase in lookups: the movie imagines the horrors of antebellum slavery imposed on modern Black Americans; the musical group’s name change means that its name no longer evokes a time when Black Americans were slaves.

Schadenfreude is a word-lover’s word, one that pops up in spelling bees and vocabulary tests all the time. This is partly because it’s hard to spell, and partly because it’s fun to say out loud, although its pronunciation isn’t necessarily easy to discern for an English speaker. In fact, this entry’s audio pronunciation is one of the most clicked-on in our online dictionary.

It’s pronounced /SHAH-dun-froy-duh/, by the way.

But this word is perhaps also popular among wordies because of its specific and slightly malicious meaning: “enjoyment obtained from the troubles of others.” It had a spike in lookups in March when news of the collegiate admissions scandal broke, but the biggest single spike this year took place on October 2nd, when it was announced that President Trump had contracted the novel coronavirus. An example of this use came in the form of a headline from USA Today:

President Donald Trump's coronavirus infection draws international sympathy and a degree of schadenfreude

Such uses created a spike of 24,800% compared to last year's lookups.

Following the announcement of President Trump’s loss to Joe Biden, the word again returned to a high spot in our list.

Schadenfreude belongs to a class of German borrowings that highlight that language’s penchant for referring to complex ideas in a single, though lengthy, compound word. It comes from Schaden, meaning “damage,” and Freude, meaning “joy.”

Asymptomatic

In this year when the public’s mind has so often been focused on COVID-19, the word asymptomatic is a reminder of one of the coronavirus’ most challenging characteristics—that people who are without symptoms can be contagious.

The word asymptomatic was looked up 1,688% more this year than it typically is. We define the word as “presenting no symptoms of disease.” It was formed in the middle of the 19th century to contrast with symptomatic, a word that predates it by more than a century. Both words can be traced back to Greek sympiptein, meaning “to happen.” The prefix a- means “not; without.”

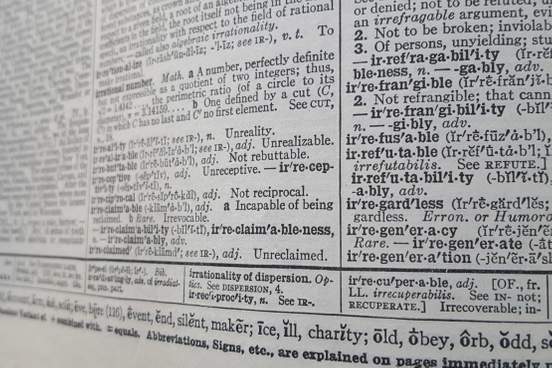

Irregardless

When all was said and done in 2020, the word irregardless had earned a spot in the Words of the Year pantheon—mostly just by having the temerity to be a word. While some will deem the word’s presence in this list as further evidence of how truly odious the year was, we in the dictionary business know that the word qualified for inclusion here because people care about language, and that’s worth celebrating.

Lookups for irregardless increased dramatically in July, up 464%, when actress Jamie Lee Curtis asserted on Twitter that we had just entered the word. Ms. Curtis was wrong: we first entered irregardless in one of our dictionaries in 1934, and an entry for it has been at Merriam-Webster.com since the dawn of that website. (Wrong or not, Ms. Curtis, we still love you.) Other celebrities tweeted about the word as well, helping to boost irregardless into a level of lookup significance that we couldn’t ignore.

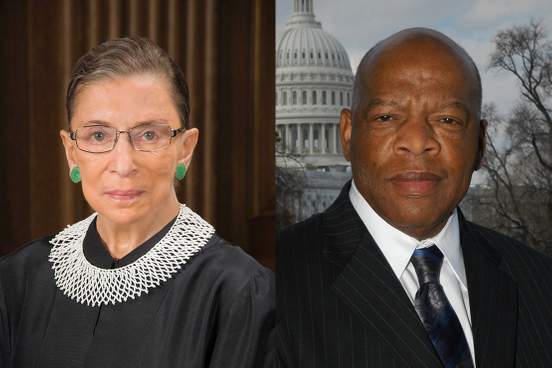

Icon

Among those lost in a year of many painful losses were two individuals whose life’s work persisted long after they’d earned a restful retirement. As writers sought to eulogize first Representative John Lewis in July, and then Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg in September, they called upon the word icon to do so. The word saw significant increases in lookups in both instances, averaging 2,205% higher than last year.

A person who is identified as an icon is widely admired for having great influence or significance in a particular sphere, and frequently also representative of some ideal. Like many human icons, the word’s beginning was a modest one: in earliest use it referred simply to an image. Eventually, it referred specifically to an image of religious value, an icon being a sacred image, often one painted on a small wooden panel and used by Eastern Christians in their prayer and worship.

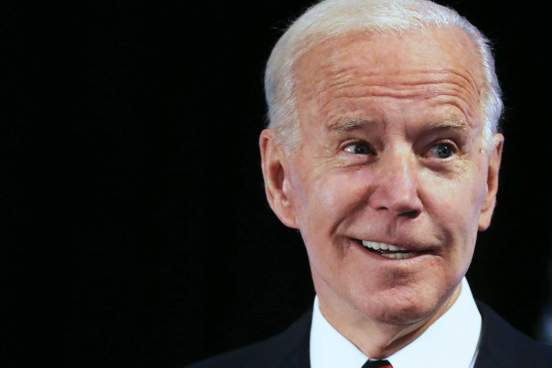

Presidents can propel a word into the common vernacular—or at least the public eye. Ronald Reagan’s verbal tic of beginning responses with “Well…” and George W. Bush’s malapropism misunderestimated qualify, and President-elect Joe Biden’s use of malarkey is on track to do the same.

Biden used malarkey several times during the vice-presidential debate with Paul Ryan in October 2012, sending many people to the dictionary to look the word up. He used it again during the 2016 Democratic National Convention, saying, of then-candidate Donald Trump:

He is trying to tell us he cares about the middle class. Give me a break. That is a bunch of malarkey.

The word’s biggest increase in lookups in 2020 was when Biden used it during the presidential debate on October 22nd, when it spiked 3,200% over last year.

It’s clear that this word is a favorite of Biden’s. In fact, our research shows that he is quoted using it going back to at least 1983, and it has since become part of his personal rhetorical style. The word seems to resonate with Biden’s public image: folksy, a bit old-fashioned, and Irish-American.

In fact, the word's true origins are not clear. It resembles an Irish last name (sometimes spelled Mullarkey), but could also have come from Irish slang or even a similar-sounding Greek word. One thing is certain: malarkey was used first in the U.S., not Ireland. We trace its earliest use back to the 1920s.

The informal and even euphemistic nature of malarkey may account for some of the visits to the dictionary’s pages, which likely aim to answer the very basic question: “is that word in the dictionary?”