We have a good number of godly words in English; mercurial (“changing moods quickly and often”) comes from the god Mercury, cereal from the name of the ancient goddess of agriculture (Ceres), and the month of January takes its name from the deity Janus (who had two faces, and served thus as the god of doorways and beginnings). The above deities are all from the Roman pantheon, but we have a fair number of words which are named after the ancient Greek gods as well. Panic, for example.

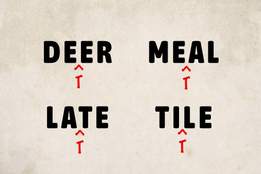

'Panic' comes from the name of the Greek god Pan, who supposedly sometimes caused humans to flee in unreasoning fear.

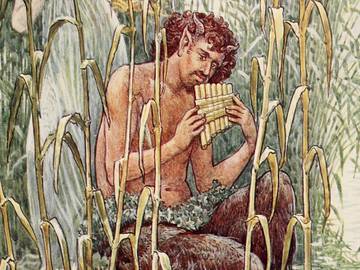

Panic comes from the name of the ancient Greek god Pan, who is also reputed, in a very unsurprising twist, to have been the inventor of the panpipes. And although Pan is frequently depicted as a bacchanalian deity, one given to near-constant pursuit of revelry and female companionship, he also had a somewhat more ferocious side.

Pan was possessed of a stentorian voice, and it was said that when the ancient Greek gods were battling a horde of giants that Pan’s shout was so overwhelming that it instilled fear in the gods’ opponents, aiding in their eventual victory. He was said as well to have occasionally caused humans to flee in unreasoning fear, which is where the commonly used sense of panic comes from.

This word existed in English as an adjective before it saw use as a noun (there is a noun sense of panic that precedes both of these words, but it is a term for a kind of grass, and is not etymologically related to the Greek god), with use dating back to the end of the 16th century. In its early use the adjectival form of panic was often found modifying such words as fear, fright, or terror.

And when as the first charge was ready to be giuen, and before they came to handy-strokes, all Izates souldiers forsooke him, and turning their backes to their enemies, fled in great disorder, as if they had been surprized with a Panique feare.

—Flavius Josephus (trans. By Tho. Lodge), The Famous and Memorable Workes of Josephus, 1602….there hapned in the night a sudden feare and fright among them without any apparant cause, such as they call Panique Frights, wherewith being woonderfully troubled and scarred, they went a shipboord, without all order….

—Plutarch (trans. By Philemon Holland), The Philosophie, 1603

By the early 17th century panic had already jumped from one part of speech to another, and began to be used as a noun.

The first Accidentall feare is that, which befalles to multitudes at once, yea euen to a whole campe of hardic souldiours: which kinde of feare is termed Panick, etymologized of Pan, because he being Bacchus his Lieutenant in the Indian war, with Art and politick stratagems, almost beyond wit surprized them with great feare and wonder.

—Vaughan William, Approved Directions for Health, both Naturall and Artificiall, 1612

It appears that taking on this additional part of speech proved wearying to panic, as the word needed to rest for quite a while before it continued to spread its semantic duties; we do not see evidence of it being used as a verb until the end of the 18th century.

Their point was to gain Time, and fall with double and united Force on a distracted and impoverished Kingdom, dismantled of her veteran Troops, panicked with the Dread of an Invasion, and intimidated with a superior Fleet, and to end it as a Blow.

—(Gloucestershire freeholder), The Crisis, 1780

In the early 20th century panic took on yet another distinct meaning, “something very funny.” This meaning, so at odds with the sense in which it had mostly been used for centuries, is a fitting one for a word which has descended from a god whose nature provoked both merriment and fear.