What to KnowPlatonic relationships are those characterized by friendship and lacking romantic or sexual aspects (in contrast with romantic relationships). They are named after Plato and reference his writings on different types of love. The term platonic was initially used to mock non-sexual relationships, as it was considered ridiculous to separate love and sex, but eventually this connotation faded away, leaving us with today's notion of close friendships.

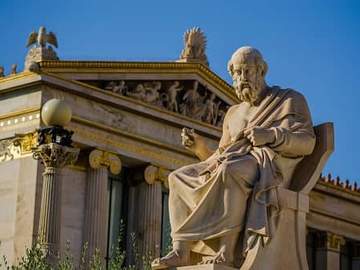

Any student of Western philosophy is familiar with Plato, who along with Socrates and Aristotle formed a trio of pillars shaping ancient Greek thought. Plato was born in the 5th century BCE and was a student of Socrates; he went on to become the teacher of Aristotle and founded The Academy in 380s BCE Athens.

The symposium will begin shortly.

Many of Plato's writings feature Socrates as a character and are presented as dialectics, giving rise to the notion of the Socratic method of inquiry. Plato established a philosophy based around the notion of ideal forms, stating that all ideas exist in a pure form apart from the material world. From this philosophy comes the notion of a platonic ideal. When that phrase is encountered in English, it often represents something visualized without the imperfections of real life:

But, of course, Gillian was right, the village was like a Platonic ideal of a village—a packhorse bridge, a beck, skirted with yellow flag irises, that threaded its way among the gray stone houses, the old red telephone box, the little postbox in the wall, the village green with its fat white sheep grazing unfettered.

— Kate Atkinson, Case Histories, 2004

In a more roundabout way, we also have Plato to thank for an adjective that we use in English to describe relationships that stay within the bounds of friendship and never turn romantic: platonic.

The bedrock of every healthy relationship, whether it’s platonic or romantic, is a mutual interest in the other person’s well-being (having a few laughs never hurts, either).

— Sam Blum, Lifehacker, 9 Feb. 2021Amber and Eddie’s friendship blossoms as the two start fake dating in order to throw off their bullies. Their relationship is the emotional core of the film, capturing how platonic love can be just as intense and messy and significant in shaping who we are as a passionate romance.

— Tracy Brown, The Los Angeles Times, 11 Nov. 2020

Why Is Friendship "Platonic"?

How did a word for a philosophical ideal come to be used for an unromantic relationship?

In Plato's Symposium, Socrates and several other figures, including the playwright Aristophanes and the aristocrat Phaedrus, who figures prominently in another of Plato's works, attend a banquet and give speeches in praise of Eros, the god of love and desire. Socrates, delivering his speech last among the group, recalls the words of a priestess named Diotima. All creatures desire immortality, she explained to Socrates, adding the idea of a ladder as a metaphor for the spiritual growth experienced by a lover. At the bottom rung is physical attraction to a particular beautiful body, followed by desire for all beautiful bodies, love for beautiful souls, for beautiful laws and institutions, and then the beauty of knowledge. At the top of the ladder is love for beauty itself, and to arrive at an understanding of the notion of absolute beauty ("a beauty which if you once beheld, you would see not to be after the measure of gold, and garments, and fair boys and youths, whose presence now entrances you") is the ultimate inspiration.

Christian Influence

This episode was recalled by the 15th-century Florentine theologian Marsilio Ficino, whose studies and translations of Plato's writings brought the philosopher's work to the forefront of Renaissance thought (a branch of what is termed Neoplatonism, in which Plato's teachings were modified by Aristotle and subsequent thinkers). In 1469 Ficino published his commentary on the Symposium, and in so doing coined the term amor platonicus, interpreting Plato's writings through a Christian lens. Ficino believed that the ladder's ultimate rung, the love for beauty itself, was made manifest through a love for God and that a true love between two individuals was drawn through a uniting of their souls.

[T]he passion of a lover is not quenched by the mere touch or sight of a body,” he wrote, “for it does not desire this or that body, but desires the splendor of the divine light shining through bodies, and is amazed and awed by it … For this reason lovers never know what it is they desire or seek, for they do not know God Himself … [It] often happens that the lover wishes to transform himself into the person of the loved one. This is really quite reasonable, for he wishes and tries to become God instead of man; and who would not exchange humanity for divinity?

Satirization

This theory of spiritual communion, or Platonic love, was viewed by artists of the day as an ideal that bordered on the ridiculous, and as English royalty and nobility embraced Neoplatonism in the 16th century, it became a convenient target of farce in poetry and literature. By the 1630s the adjective Platonic (eventually uncapitalized) had seen use in English in the "nonsexual love" sense that we know today.

The trend toward Platonic influence was sent up in The New Inn, a 1631 satire by dramatist Ben Jonson that marks the first use of the "spiritual rather than physical love" sense documented in the OED. Much of the plot of The New Inn concerns discussions over the nature of love and includes a courting session that is thrown into chaos and confusion by means of cross-dressing and characters concealing their identities.

Five years after The New Inn was published, Sir William Davenant published The Platonick Lovers, another stage farce that mocks the idea of Platonic love by contrasting the love of two characters, Theander and Eurithea, as impossibly lofty in contrast to the more carnal-oriented desires of Phylomont and Ariola.

Later writers continued to employ platonic as a contrasting word, often with the underlying suggestion that love separated from sexual desire was an absurd pretense:

And every beau would have his jokes,

That scholars were like other folks;

That when Platonic flights were over,

The tutor turned a mortal lover.

— Jonathan Swift, The Battle of the Books, 1704That refined degree of Platonic affection which is absolutely detached from the flesh, and is, indeed, entirely and purely spiritual, is a gift confined to the female part of the creation; many of whom I have heard declare (and, doubtless, with great truth), that they would, with the utmost readiness, resign a lover to a rival, when such resignation was proved to be necessary for the temporal interest of such lover

— Henry Fielding, Tom Jones, 1749Cradell, however, seemed to think that there was no danger. His little affair with Mrs. Lupex was quite platonic and safe. As for doing any real harm, his principles, as he assured his friend, were too high. Mrs. Lupex was a woman of talent, whom no one seemed to understand, and, therefore, he had taken some pleasure in studying her character. It was merely a study of character, and nothing more. Then the friends parted, and Eames was carried away by the night mail-train down to Guestwick.

— Anthony Trollope, The Small House at Allington, 1862He would not have it that they were lovers. The intimacy between them had been kept so abstract, such a matter of the soul, all thought and weary struggle into consciousness, that he saw it only as a platonic friendship. He stoutly denied there was anything else between them. Miriam was silent, or else she very quietly agreed. He was a fool who did not know what was happening to himself. By tacit agreement they ignored the remarks and insinuations of their acquaintances.

“We aren’t lovers, we are friends,” he said to her. “We know it. Let them talk. What does it matter what they say.”

— D. H. Lawrence, Sons and Lovers, 1913

Modern Usage

Gradually, the sneer of contempt that accompanied use of platonic thinned out, as did the association with spiritual connection. Platonic then settled into a meaning closer to a serious idea of friendship, particularly among people who could just as easily be romantic partners. But even today, however, the word sometimes raises eyebrows when invoked. Just ask anyone who has shown up to a party with someone who's introduced as strictly a friend, only to be pulled aside later and asked: "You and [x] … what's going on there?"