Gridiron

Gridiron has been used colloquially to refer to the American football field since 1890, when the game we know as American football started growing in popularity. Our first recorded use of the "football field" meaning gives us a hint as to where gridiron came from:

Tom Stokes—Who was the first man killed at foot-ball?

Jim Hickey—St. Laurence, I suppose; he died on the “gridiron.”

— Puck (New York, NY) 5 Nov. 1890The gridiron football field is an absolute monarchy. The captain of the eleven is the reigning czar, and the coaches are the power behind the throne.

— The Boston Post, 29 Oct. 1893

The truth is, gridiron is much older than football. When the word first came into English in the 1200s, it referred to a grill grate used for torture. The St. Laurence mentioned in the 1890 joke was purportedly martyred by being grilled to death, even quipping to his captors, "I am cooked on that side; turn me over, and eat."

It wasn't the torturous play that made football players and fans think of the method of St. Laurence's demise, but the field itself. Early football fields were marked in a grid, not by the familiar parallel yard lines we know today, and the association between a grid and the word gridiron was too strong to shake. Gridiron had already been applied to other things that resembled a grill grate, so why not the football field?

Scrimmage

Football is based, in part, on English rugby, and early in American football's life, the ball was put into play the same way it was in English rugby: teams gathered in a scrummage (or scrum) around the ball and tried to kick it forward through the group of players.

The ball is seldom on the ground for any length of time at Rugby; one side or the other having it generally in their arms and struggling for its possession. When it is kicked out at the sidelines, the player who first touches it has to bring it to the edge, where the two sides spread out, facing each other to catch it, and, as soon as caught, there is another scrummage.

— Chamber’s Journal (London, Eng.), 12 Mar. 1864

Harvard was the first to change this: in the 1870s, they opted for heeling it out—kicking the ball backwards to a teammate instead of trying to move it forward. Walter Camp, a student at Yale who played football from 1876–1881, refined the heel out scrummage even more. He put in place a rule that favored a scrimmage rather than a scrum: possession of the ball alternated between teams and didn't rely solely on the winner of the scrum. In short order, American football players began assembling in two facing lines at the "line of scrimmage," where play began. The first use of scrimmage to refer to this way of starting play was in the Harvard Advocate in 1880.

If scrimmage sounds a little more orderly and prim than a scrum, that's an illusion. Scrimmage is an alteration of the medieval English word skyrmissh, which we recognize as skirmish, and our earliest uses of scrimmage refer to either a minor battle between two small armies, or a free-for-all brawl. Scrummage itself is an alteration of scrimmage.

Down

Just like Camp created the line of scrimmage and the idea of uncontested possession in American football, he also created the down.

In American football, the word down has a few different uses. Each team gets four downs, or attempts to advance the ball ten yards up-field. This is the down that gets the ordinal number attached to it—as in first down, second down, third down, and fourth down—and is the down that's implied in shorthand constructions like "2nd and 10" (second down with ten yards to go). When a team advances the ball ten or more yards in one play, they have made a down. It can also refer to the point at which play stops when a player can no longer advance the ball, either because they've been tackled ("He's down at the 45") or because an official or the player has intentionally stopped play ("Manning downed the ball with 3 seconds left on the clock"). And, of course, there's the touchdown, a method of scoring that football borrowed from rugby, in which the ball is "touched down" across the opponent's goal line.

These last uses of down hint at the origins of the play's name. A ball that is down on the ground is out of play.

Walter Camp invented the down system as a reaction to two games between Princeton and Yale in 1880 and 1881, when Princeton held the ball for a full half and both games ended in a scoreless tie. This was permissible in early football (as it is in some forms of rugby), but it frustrated Camp, who, it must be said, played for Yale during this era.

Hail Mary

Football fans know that when the clock is ticking down to the end of the 4th quarter and there's nothing left to an offense, they can always try for a Hail Mary. The Hail Mary is a long forward pass that's thrown into or near the end zone as a last-ditch attempt to score as time runs out.

The only misses for the weekend were the recommended Hail Mary plays on the first touchdown scorer in the Green Bay Packers-Dallas Cowboys game.

— Neil Greenberg, Philadelphia Tribune, 19 Jan. 2024

Hail Marys (and not "Hail Maries") are plays of desperation. According to the NFL archives, the play that popularized the term was the final offensive push by the Dallas Cowboys in the 1975 NFC Divisional Playoff game against the Minnesota Vikings. The Vikings were up 14-10 with 0:32 seconds on the clock; Dallas had possession of the ball at their own 45-yard line. As the Cowboys lined up for the play, the game commentator quipped, "Well, the Cowboys need a miracle."

Roger Staubach, Cowboys quarterback, delivered it. He threw a 50-yard pass to Drew Pearson, who caught it on his hip at the five-yard line and trotted it in for a touchdown. Staubach recounts being asked after the game what he was thinking and answering, "I closed my eyes and said a Hail Mary."

While this use of Hail Mary may have been popularized by Staubach (a devout Catholic), the term had already been in use with other football players (as both Hail Mary pass and Hail Mary play) for a number of decades.

Or there's the classic bowser about the Hail Mary play, the one about the coach who at a skull drill suddenly snaps at the fourth string quarterback, "What would YOU do under these circumstances?" not to mention the famous "why-don’t-you-show-him-your-scrapbook?" gag.

— The Boston Globe, 8 Oct. 1935McFadden—a great actor in the huddle—is willing to call any play from a straight line buck to a "Hail Mary" pass with never a thought of the second-guessers.

— The Tampa Bay Times, 31 Dec. 1940

Sack

In order to throw a successful Hail Mary, the quarterback needs to buy some time for the receivers to get down-field. But the longer the quarterback holds on to the ball, the higher the chances of a sack.

In football, sack refers to an instance of tackling the quarterback behind the line of scrimmage. The term was, as far as we can tell, coined by David "Deacon" Jones, one of the NFL's most famous defensive linemen. He coined the term in the 1960s, when he was part of the Los Angeles Rams' "Fearsome Foursome." Here's Jones on why he called taking down a quarterback a "sack":

Sacking a quarterback is just like you devastate a city or you cream a multitude of people. I mean it's just like you put all the offensive players in one bag and I just take a baseball bat and beat on the bag.

Jones' bite was as fearsome as his bark—he's considered one of the game's greatest pass rushers of all time. And sack was an appropriately destructive term to borrow. The verb doesn't just refer to plundering a town for spoils (by bagging up, or sacking, everything) after its capture, but sack was formerly used to refer to executing a condemned person by sewing them up into a sack and drowning them.

Blitz

There are not many defensive plays that get their own interesting names—the sack is one, and the blitz is another. A blitz is when a defensive player (like a linebacker, back, or end) abandons their normal position to rush the passer. A blitz might involve more than one defensive player, and it might result in a sack. The goal is to disrupt a passing play and take the quarterback off-guard.

The word blitz is a shortened form of the word blitzkrieg, which English borrowed from German. The original blitzkrieg was a short and violent military attack intended to produce as much damage (both material and psychological) as possible. Blitzkriegs (or blitzes) were used by German forces during World War II and became associated with Nazi military tactics. The period in 1940 of heavy nighttime air raids in London came to be called "the Blitz" for the raids' sudden destructiveness. Blitzkrieg literally translates from the German as "lightning war."

The words blitzkreig and blitz were not borrowed into English until the end of the 1930s, but it did not take more than a few years before both began to be utilized in broadened fashion by sportswriters describing football.

With 30 men on hand at the end of the first week of preliminary drill, Coach Eddie L. Jackson, Johnson C. Smith University football mentor, will move his celebrated Golden Bull Brigade into heavy practice this week as the Bulls prepare for a blitzkrieg of the CIAA gridiron this fall.

— Milton C. Branch, The Philadelphia Tribune, 20 Sept. 1941With Leland college's conference champions as the season’s opener scheduled for Saturday afternoon, September 27, in Southern stadium, Coach Mumford and his aides are sending their 1941 football edition through stiff paces in order to be ready for the onslaughts of Coach Turner's blitz.

— E. James Hamilton, The Atlanta Daily World, 24 Sept. 1941

Everything about the Super Bowl is, well, super: the teams, the play, the halftime shows, the commercials, the ticket prices. It's no surprise that it's called the Super Bowl. But Bowl?

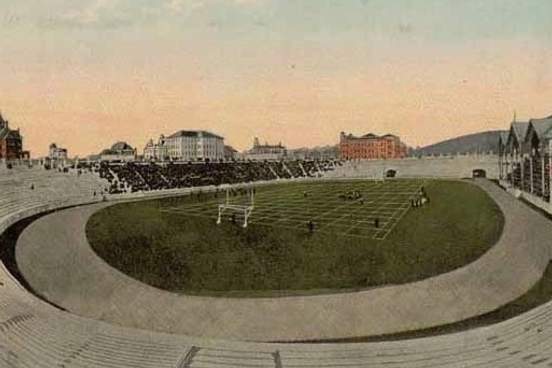

The word bowl came to be used generally of a postseason football game between specially invited teams in the 1930s, but bowl games themselves go back to 1902. In that year, the Tournament of Roses in Pasadena, California, invited Stanford University and the University of Michigan to play a New Year's Day football game as part of the amateur athletic events that followed the Parade of Roses. (Michigan won, 49-0). The Tournament of Roses dropped the football game in the years that followed but reinstated it as an annual event in 1916.

The football game was held in Tournament Park until 1923, when it was first held at the newly constructed Rose Bowl stadium. The Rose Bowl stadium was one of the first stadiums in America built specifically for American football—its elliptical shape was modeled on the Yale Bowl and its name was inspired by that edifice.

The intercollegiate game known thereafter as the Rose Bowl became wildly popular—the game was good for the schools involved, as well as for the businesses of Pasadena—and other collegiate Bowls soon followed.

Professional football, meanwhile, stayed out of the bowl business for most of its early history. When the National Football League and the rival American Football League began merging in 1966, they wanted to have a postseason championship game between the top teams of the two leagues. The game was originally known as the AFL-NFL Championship Game, but that unwieldy name was dropped in 1969 when the NFL-AFL merger was nearing completion. Borrowing from the familiar jargon of college football, the now-unified NFL called their pro championship game the “Super Bowl.”

Muff

The punter kicks; the punt returner prepares to field it; the returner muffs it. No, the returner hasn't caught the punt and tucked the ball into "a warm tubular covering for the hands"; they've attempted to catch the ball but didn't. This is different than a fumble, which is when the ballcarrier has possession of the ball and then loses it. When someone muffs a punt or a pass, they never had possession of the ball in the first place.

Michigan muffed a punt that gave Alabama the ball in Wolverines territory, missed an extra-point attempt on a bad snap, missed a field-goal try, averaged just 39.5 yards per punt and muffed a second punt in the game’s final minute that nearly lost the game.

— J. Brady McCollough, The Los Angeles Times, 6 Jan. 2024

The verb muff first showed up in English writing in the early 1800s to refer to awkwardly handling something. Our first sports use is in cricket: a complaint about players who "muffed their batting." The sports use took off and was applied to golf, baseball, and finally to football. The verb has broadening in meaning, and now can refer to messing anything up.

Two maiden overs were then bowled, but in the next Butler made 2 to the leg, and then a single, whilst in that which followed he "muffed" a ball, which was within an ace of being caught by Dorrinton in the slips.

— The Standard (London, England), 8 Sept. 1845Reynolds gave Merrill another chance, but he muffed the ball and Reynolds took his place on first.

— The Louisville Daily Journal, 6 Aug. 1868Soon after this Cabot muffed the ball at a critical point, and Yale was kept from making another touch-down only by a splendid tackle by Morison, of Harvard.

— The New York Times, 26 Nov. 1882

Any connection to the tubular covering for the hands? Etymologists believe so. Wearing one meant the hands were inaccessible, and trying to handle anything while wearing one would be awkward at best.

If a team doesn't make a down in their four down attempts, then they have the option to punt on their fourth down—that is, they can kick the ball to the opposing team.

On third-and-3 from the Dolphins' 48-yard line, Patrick Mahomes tossed a deep pass to Mecole Hardman. While Hardman was tracking the football, Dolphins safety Brandon Jones clearly grabbed the wide receiver’s jersey as the ball sailed over Hardman's head incomplete. Hardman and Mahomes were visibly frustrated over the non-call as the Kansas City crowd booed. The Chiefs were forced to punt the football away.

— Tyler Dragon, USA Today, 13 Jan. 2024

We tend to think of a punt as a long kick, but that's not what makes a punt a punt. The defining characteristic of a punt is that the punter drops the ball from their outstretched hands, and must kick the ball with the top of their foot before the ball hits the ground. A good punt is long—the objective is to send the ball as far towards the opposing team's end zone as possible, so they are in a worse starting position when they take possession of the ball.

Etymologists are unsure of where we got punt. We know that it first appeared in written English in 1845, in the football rules issued by the Rugby School, but there's nothing in that citation that gives us a hint as to its origins. The two prevailing theories are that punt is an alteration of the earlier verb bunt, which at that time meant "to strike or push with the head," or that it's borrowed from another verb punt that was regional and meant "to push with force." But there are problems with both theories. We don't have written evidence of the regional verb punt until after 1845, which presents a chronology problem for us, and the initial verb bunt was used primarily of animals (and particularly sheep) butting each other.

Sudden Death

There is nothing like the agony and ecstasy of a tied game at the end of the fourth quarter. You had hoped your team would prevail in regulation play, but you also know that both teams will try to play their best during overtime. It is sudden death.

Sudden death goes back to the 14th century, long before football was invented. Its initial meaning was literal: it referred to an unexpected death that was instantaneous and not the result of violence. It wasn't until the 1830s that it gained a new meaning: a coin toss used to decide an issue or contest. The suddenness of the coin-toss decision made sudden death the perfect phrase to describe a period of play after a regular match in which the first score immediately ends the game.

The NFL adopted sudden-death overtime in stages beginning in 1940, but no longer uses it to decide football games. In 2012, they adopted what they call "modified sudden death." Possession of the ball in sudden-death overtime was decided (appropriately) by a coin toss, and more often than not, it turned out that the team who won the coin toss was generally the winner in sudden death—all they had to do was advance the ball far enough for a field goal, which was relatively easy to do in four downs. Now, in modified sudden death, the teams have an opportunity to possess the ball at least once in the extra period unless the team that receives the overtime kickoff scores a touchdown on its first possession. If neither team scores during their initial possession in overtime, then the game goes to proper sudden death.

12th Man

Much has been made in recent years of the 12th man—the importance of their influence, their perseverance, their loyalty. But even a casual football fan knows that there are only 11 players per side on the field. Who is this 12th man?

Eminem has almost unofficially become the Lions "12th man" during the playoffs at Ford Field and he delivered again at last night's game versus Tampa Bay just at the right moment.

— Edward Pevos, MLive.com, 22 Jan. 2024

The 12th man is the fan, and in the NFL, the phrase is now most commonly associated with the Seattle Seahawks, who now generally refer to their fanbase as the 12s (a gender-neutral version of the 12th man). The fan support has had a huge impact on opponents who play the Seahawks at home. In 2005, fans notoriously rattled the New York Giants enough that they committed a whopping 11 false-start penalties and missed three field goals for a loss. In 2013, fans at Seattle's CenturyLink Field broke records during a game against the New Orleans Saints, where the crowd noise registered 137.6 decibels—only 2.4 decibels quieter than an aircraft carrier's deck, and only 12.4 decibels short of eardrum rupture.

But the phrase predates the Seahawks by 76 years: it was first used in Minnesota Magazine in 1900 in an editorial about college ball: "The mysterious influence of the twelfth man on the team, the rooter, should be as great as any of the rest." As football increased in popularity, so did the phrase 12th man.

The phrase is historically associated with Texas A&M. The 12th man is a long-standing Aggie tradition: Aggie fans have taken up 12th man in honor of E. King Gill, a squad player for A&M who was called down from the press box during the 1922 Dixie Bowl and stood on the sidelines, ready to help the injury-ridden Aggies should he be called upon. Gill's support and encouragement became the stuff of legend. It helped that 12th man was already known to A&M fans: it showed up in a 1921 article in the A&M The Battalion that talks of the psychological impact of "the old yelling army … the twelfth man."

Texas A&M actually holds the trademark to the 12th man in reference to fans, which led to a legal scrape between A&M and the Seahawks. In 2006, the suit was settled out of court; the Seahawks could continue to use the phrase of its fans, but only under license from A&M.

Wing Back Formations

There are few things more mortifying than showing up at one’s in-laws, or any other potentially inhospitable environment, and committing a football-terminological faux pas. For instance, confusing your double wingback formation with your single wingback formation, or even worse, confusing either of the above with the plain wingback formation. Here is how these formations differ:

Wingback: an offensive formation in football in which a back is placed just behind or slightly beyond and to the rear of an end.

Double wingback: an offensive football formation in which two halfbacks play approximately one yard outside the offensive ends and one yard behind the line of scrimmage.

Single wingback: an offensive football formation to the left or right in which a back plays just outside of and a yard behind one of the ends, the blocking back is on the same side of the center and usually a yard behind the guard, and the two other backs are four or five yards behind a balanced or unbalanced line and in a position to receive a direct snap from the center.

We record double wing as a variant of double wingback formation, and single wing as a variant of single wingback formation; we do not, however, offer wing as an acceptable variant of wingback formation. Please commit this to memory.