There is no such thing as “the dictionary”

We often hear people refer to any alphabetically organized book of defined words (especially if they think it supports their position) as “the dictionary.” This hurts our feelings, for it makes it sound as though there was only one such book, and all the lexicographers out there, toiling away for years on end to craft careful explanations of hundreds of thousands of words, are all just repurposing some master list, perhaps by changing the font, or putting a new cover on an existing book.

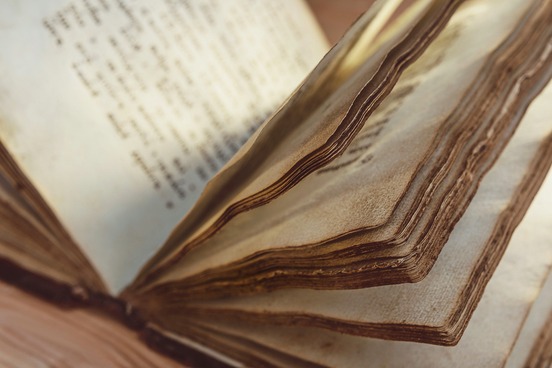

A great number of English dictionaries have been published since Robert Cawdrey first released his A Table Alphabeticall in 1604. How many? Well, it is not possible to give an exact number, but in Arthur Kennedy’s 1927 Bibliography of Writings on the English Language he lists well over 500 published between 1604 and 1922. Almost all of these are general monolingual works, and there are thousands of other dictionaries that deal with slang, learner’s English, and specialized fields.

Every one of these dictionaries is different from the others. They differ in scope and ambition, in terms of the geography and register of the language they cover, and in terms of accuracy.

Lexicographers do not decide what is a word

While it is appealing to imagine that there is some tribunal of lexicographers who gather in a clandestine meeting every year, perhaps wearing scarlet robes and some sort of silly hat, in order that we might machinate and scheme, deciding which foul and loathsome new words we are going to release on an unsuspecting public, the truth is that dictionaries do not work this way.

The criteria for inclusion varies from one dictionary to the next, but for the most part, words are added (or removed) based on data. If enough people use a certain word in a certain way for a certain length of time (or if it has substantial currency in a particular field, such as medicine) it will be added to a dictionary.

Putting a word in a dictionary does not mean that lexicographers approve of it

The fact that we (or any other dictionary) include certain words and offer definitions for them should not be seen as a call to go out and pepper your speech and writing with irregardless, OMG, and ain’t. Similarly, the fact that we include \ˈnyü-kyə-lər\ as a variant pronunciation for nuclear does not mean that we are instructing you to say that word this way. We include these words and these variant pronunciations because there is a large body of evidence attesting to their use among people who write and speak the English language.

In many cases we will also include notes, specifying that these words and variants are shunned by some portion of the population, or explaining that they are regional forms. If you would like to better understand our usage notes you may find them here, and our guide to pronunciation may be found here.

The order of the definitions may not mean what you think

Many words have multiple senses, and it is therefore necessary to arrange them in some sort of order. The significance of this order will vary from dictionary to dictionary, and from publisher to publisher, and it can all be a bit confusing (our Learner’s Dictionary gives the most common sense of a word first, and our Unabridged tends to give the oldest sense first). The one thing you should remember, however, is that the first sense presented to you is not, as is commonly assumed, the most ‘important,’ or ‘correct’ meaning. Some senses may be archaic, slang, or rare, but none are better than the others. All the senses of a word that are listed are equal, and not in a George-Orwellesque all-words-are-equal-but-some-are-more-equal-than-others sort of way.

Dictionaries are not grammar teachers

Many people conflate grammar and usage, and while there may be some overlap between the treatment of these two subjects in a dictionary, lexicographers tend to distinguish between them. Dictionary makers also tend to be not nearly as concerned with grammar as people think they should be (an impression that is based on the letters people send to us).

The reason that we include a definition for that sense of literally that makes your eyeballs hurt has nothing to do with grammar. It has to do with usage. The question of whether the genitive apostrophe came about as a result of English shifting away from being a heavily inflectional language (in which this punctuation mark stood in for certain now-discarded case endings) or whether it served as a substitution for part of the word his is an issue that might be referred to as grammatical, but literally is just a word that has taken on multiple meanings.

Since dictionaries serve as catalogs of the language they will often also deal with issues relating to grammar. However, these tend to be grammatical issues that have some bearing on the meaning of a word, rather than grammatical issues such as sentence structure.

Dictionaries do not contain all the words

Perhaps because they tend to be rather large books there is frequently an assumption that most dictionaries contain all the words in the language. The problem with this assumption is that it often leads people to then reason that if a dictionary has all the words in a language it must mean that any word not defined in a dictionary is not a ‘real word.’

The technical term for this kind of reasoning is bosh.

There has never been, and never will be, a dictionary that includes all the words in English. Some words are omitted because they are obsolete, and others are left out because they are not germane to anyone but a specialist (dictionaries tend to not define all of the known chemical compounds, for instance).

Dictionaries are all out of date

The great 18th century lexicographer Samuel Johnson said and wrote many witty things about dictionaries and the people who make them. Among these witticisms was "Dictionaries are like watches, the worst is better than none, and the best cannot be expected to go quite true.”

The science of horology has changed a considerable amount since Johnson wrote these words, as has the art of lexicography. Yet there is one constant theme in dictionaries from then until now: they are all out of date by the day they are published.

This is both inevitable and not a bad thing. In order for a word to merit inclusion in a dictionary it has to have been around for a certain amount of time, which means, of course, that for some portion of the word’s early life it will be in regular use, but not defined in any dictionary. Lexicographers rely on data, rather than gut feelings, when deciding which words will be entered and defined. Were dictionaries to be entirely up to date on all the newest words and phrases they would have to enter these as soon as they began being used, leading to reference works glutted with a profusion of coinages and evanescent slang, most of which will likely not be in use five years from now.

Dictionaries are not the stern nannies of the English language

Dictionaries in general (and Merriam-Webster in particular) have oft been accused of ‘giving up the fight.’ Which fight is that? That would be the one in which the forces of darkness and ignorance have surrounded the noble and virtuous English language and are attempting to murder it with semantic drift. The technical term for this kind of argument is piffle.

There is no fight. The English language is not under siege. It is not broken and does not need fixing. Dictionaries are not abdicating their position as defenders of the language (if only because they never had this position in the first place).

The only languages that do not change are dead languages, and the only reason they do not change is because no one speaks them anymore. Semantic change is a sign of a healthy language, not evidence that young people/journalists/politicians/some group of musicians are ruining our precious tongue. The role of the dictionary is to make note of these changes and to document them as accurately as possible. A good dictionary has the responsibility of explaining to you how other people use the language; it does not have the responsibility of adhering to some imagined standards of correctness.

Do you want your history books to tell you how history ‘should have happened,’ or would you prefer to know what actually happened? Most people are more interested in the truth, and if you would rather have an accurate portrayal of our language then stop telling lexicographers that they should be fixing the language.