Hawsehole

: a hole in the bow of a ship through which a cable passes

Nautical language is full to the gills with words you would swear to St. Elmo were naughty if you didn’t know any better. Who can forget the first time they learned what a poop deck is? Not us! Hawsehole is very clearly one such word (to hear how it’s pronounced, we recommend clicking the link above again and again). The hawse in hawsehole is the part of the ship’s bow (not its stern, mind you) that contains the hawseholes, the word hawse coming from the Old Norse word hals, referring to the same and also meaning “neck.”

The final third of The Meadowlands boasts two of the best songs of the decade. ‘Boys, You Won’t’ is a song of heartbreak, alternating between irritating static, a plinking electric piano, and a guitar that sounds like an anchor chain being pulled through a hawsehole. The effect is unnerving and intoxicating at the same time.

— Bruce Porter, DrownedInSound.com, 1 Sep. 2010

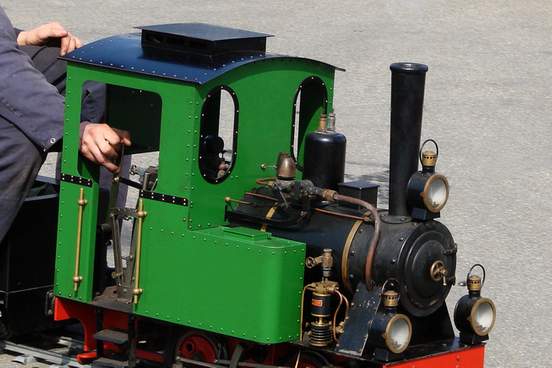

Dinkey

: a small locomotive used especially for hauling freight, logging, and shunting

As a diminutive green extraterrestrial sage once said, “Size matters not.” To the point: some locomotives are just small, and there’s nothing wrong with that. They can still haul freight, assist in logging, and even shunt, in case you had any doubts. The first known use of dinkey to refer to a wee choo choo occurred in 1874, around the same time that the adjective dinky, from which it is thought to have arisen, began to be used to mean “overly or unattractively small.” But before that dinky had a variety of synonyms, from neat and smart (as in “dashing in appearance”) to cute and pretty. It’s quite possible that some ferroequinologist (that is, railroad hobbyist) had one of those uses in mind when first they glanced upon and so dubbed the dinkey.

“I’ve been at the old man to give her a new stem and a new gland for three or four months back, but he won’t do it. Says he don’t want to put anything onto the dinkey till he gets her in the back shop; he’s going to give her metallic packing then, and he’s been telling me about taking her in in a couple of days ever since last week. That’s the song he always gives me whenever I make a kick about the valve-stem.”

— B., Locomotive Firemen’s Magazine (Volume XX, January—June, 1896)

Butoxy

: of, relating to, or containing butoxyl

You are forgiven if you assume butoxy is some regional variant of buttinski, meaning “a person given to butting in” to conversations. Or perhaps that a butoxy is “windy” according to windy sense 2 rather than windy sense 3a. Alas, it is neither of these, and in fact is not even a noun, but an adjective. And if you were to call someone a “butoxy lummox” you would simply be saying that they are a clumsy person containing butoxyl. As we all know (cough) butoxyl refers to “a univalent radical C4H9O− composed of butyl united with oxygen.” Butoxy- is also a combining form that means “containing butoxyl.”

The foul-smelling product contains 2-butoxy-ethanol, which can be toxic. Crews applying the fertilizer wear respirators and gloves.

— Marguerite Holloway, Scientific American, October 1991

Peneid

: a prawn of the family Peneidae

Who are you calling a shrimp? Now that we think of it, peneid could make a handy substitute for shrimp in many a disparaging phrase, given that peneids are prawns, and prawns resemble shrimp, both being edible decapod crustaceans. Just don’t expect to celebrate All-You-Can-Eat Peneid Night at your local chowder house anytime soon.

Fecket

Scottish : a vest

If it didn’t mean something as mundane as “vest,” fecket might make a fine put-down along the lines of flibbertigibbet—just as old-timey but pithier and perhaps a bit edgier given that fricative to start. Can you imagine an exasperated newspaper publisher in a certain spider-themed superhero comic railing “Get on with it, you little fecket” at the protagonist? Because we can.

His coat is the hue o' his bonnet sae blue,

His fecket is white as the new-driven snaw…

— Robert Burns, The Laddie’s Dear Sel’ (1798)

Crapette

: a card game in its procedure similar to most forms of solitaire but always played by two persons in which each player has his own pack of cards and attempts to play all of them while impeding the opponent’s plays

Were you to use it as an insult, crapette would be both self-explanatory and, we imagine, fairly mild—a term of endearment for a beloved yet incontinent dog, perhaps (the suffix -ette meaning “little one,” as in kitchenette). Instead crapette (from the French crapette, same meaning) is a lesser-known name for a two-person card game that goes by many others, including “Russian Bank,” “Cat and Mouse,” “Hate and Malice,” and “Spite and Malice.”

“Let’s play a game of crapette,” he suggested. “We haven’t done that in a long time.” From the dresser he took two decks of cards and started to lay them out.

—Margaretha Shemin, The Empty Moat (Putnam, 1969)

Chunter

British : to talk in a low articulate way, to mutter

Chunter is not to be confused with the Australian slang verb chunder, meaning “to puke” (see/hear the song “Down Under” by Men at Work: “… where beer does flow and men chunder”). It is also not to be confused with punter, a noun used chiefly in British English to refer to a gambler (among other things). Chunter simply means “to mutter” or “to grumble.” However, were you to be visiting Vegas and happen to see someone at a craps table toss their cookies and decide to call them a chunter, we would let that stay in Vegas.

They chuntered away, all the time, those two. But when Sam drew close and overheard them, there seemed neither beginning nor middle nor end to it. Buster would throw in some of his experiences as a bus driver; Yoke would ramble on about sheep or turnips; but mostly they would chatter through what had happened to them during that day.

—Melvyn Bragg, The Soldier’s Return (Arcade, 2002)

Dunkadoo

: a large North American marsh bird (Botaurus lentiginosus) that is related to the herons and has a brown body, dark gray outer wings, and a black stripe down each side of the neck

As we suggested in the first volume of this series of non-insults, there are many, many, words for birds—both common and scientific, that would make excellent epithets for sniping (cough). Dunkadoo, a dialectal name for the American bittern, is no exception, though admittedly a bit milder than, say, bushtit. American bitterns are secretive, somewhat chonky marsh birds related to herons, and produce a distinctive call by repeatedly inflating their throats that some* have decided sounds like “dunk-a-doo,” hence the moniker. Other nicknames for the American bittern are just as fun to say (or call someone) include stake driver and thunder pumper, the latter of which is sometimes shortened to thunderpump.

* Clearly not including Henry William Herbert, as noted in the quote below.

“The bird, when fat, is considered by many to be excellent eating.”

It is on the strength of Mr. Wilson’s statement as above that I have given among the vulgar appellations of this beautiful bird that of Dunkadoo; though I must admit that I never heard him called a Dunkadoo, either on the sea-coast of New Jersey or any where else; and further must put it on record, that if the sea-coasters of New Jersey did coin the said melodious word as imitative of its common note, they proved much worse imitators than I have found them in whistling bay snipe, hawnking Canada geese, or yelping Brant. They might just as well have called him a Cockatoo, while they were about it.

— Henry William Herbert, American Game in Its Seasons (Charles Scribner, 1853)

Vug

: a small unfilled cavity in a lode or in rock

If calling someone a vug sounds like a prime dig, you may be remembering the “Vug under the rug” from Dr. Seuss’s There’s a Wocket in My Pocket, which, frankly, still terrifies us. The vug as invoked by geologists and attested in our dictionaries is not that vug, alas, though you could have a vug under your rug if your floor is bare rock that contains a small, tectonically produced, crystal-lined fissure. Vug is a modification of fugo, meaning cave, akin to Old Cornish’s vooga.

Now in Paterson, Deffeyes searched the roadcut vugs (as the minute caves are actually called) looking for zeolites. Some vugs were large enough to suggest the holes that lobsters hide in.

—John McPhee, Basin and Range (The Noonday Press, 1981)