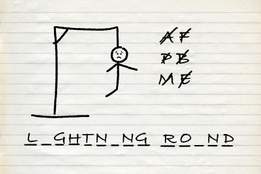

Will 'ect.' become an acceptable spelling of 'etc.'? And if it does, will that be unexplainable or merely inexplicable?

Spellings—such as 'ect.' for 'etc.'—that reflect alternative pronunciations, and the unexplainable favoritism that is shown to inexplicable.

Hosted by Emily Brewster, Ammon Shea, and Peter Sokolowski.

Produced in collaboration with New England Public Media.

Download the episode here.

Transcript

Emily Brewster: There are no words in either French or English that begin with E-T, except for et cetera.

Peter Sokolowski: Inexplicable and unexplainable both have Latin roots and they still occupy the same lexical space.

Emily Brewster: Coming up on Word Matters, spellings that reflect alternative pronunciations, and the unexplainable favoritism that is shown to inexplicable.

Emily Brewster: I'm Emily Brewster, and Word Matters is produced by Merriam-Webster in collaboration with New England Public Media. On each episode, Merriam-Webster editors Ammon Shea, Peter Sokolowski, and I explore some aspect of the English language from the dictionary's vantage point.

Emily Brewster: A listener question about E-C-T as used for the abbreviated form of et cetera, or rather, a version of that Latin phrase pronounced as "excetera," raises questions about other alternative spellings that develop to reflect nonstandard pronunciations.

Emily Brewster: I'll start our discussion off.

Emily Brewster: Listener Michael wrote in response to our segment on abbreviations saying, "I listened to this episode hoping all along that you would address E-T-C, the abbreviation for et cetera. With so many people pronouncing it "excetera" these days, along with other words such as "exspecially," the abbreviation has started to morph toward E-C-T. I see it all the time now. You could have killed two birds with one stone by correcting the pronunciation along with the spelling of the abbreviation."

Emily Brewster: So what of that spelling and pronunciation of the abbreviated form of et cetera?

Emily Brewster: Well, Michael May be both heartened and disappointed. We don't include E-C-T as a spelling of the abbreviation in our dictionaries, but we do include the pronunciation "excetera," and it was added quite a while ago now; in 1993, for the 10th Collegiate Dictionary.

Peter Sokolowski: It doesn't surprise me at all.

Emily Brewster: Why?

Peter Sokolowski: Because I think, even though Michael's attention to detail and care for language are laudable, I think there's also something else going on in his case, which is what we sometimes call the recency effect, which is that you notice something and then you start to notice it everywhere and you think it's new, but actually this, I think, is something that's been going on for a long time.

Emily Brewster: Yes, possibly. It could also be that it is becoming more and more common too.

Peter Sokolowski: Yes. And that there's more non-professionally edited writing that we all encounter every day.

Emily Brewster: Yes, absolutely. I think it is just so remarkable, the amount of unpublished text that we see now as human beings and how completely unprecedented it is. We have never had so much access to the printed word.

Ammon Shea: We're in a golden age of unedited prose, to put it one way. We always try to look on the positive side.

Emily Brewster: Now, in our dictionaries, the "excetera" pron is labeled nonstandard. And by "nonstandard," we mean that we've got plenty of evidence of it in use, but it's widely disapproved of. So it's a sort of warning to the reader that, "You know, if you use this pronunciation, it's going to stand out to people, and people might think that you're saying it incorrectly."

Emily Brewster: The dictionary is not saying you're saying it incorrectly, but the dictionary is saying that you are saying in a way that is not the standard way of saying it.

Emily Brewster: Here's an interesting thing; our usage dictionary, Merriam-Webster's Dictionary of English Usage, has an article on this pronunciation of et cetera. And it says that the variant pronunciation is common in both English and French because of assimilation, which is a technical linguistics term that means "the change of a sound in speech so that it becomes identical with or similar to a neighboring sound."

Emily Brewster: And we use assimilation in phrases all the time. So if you say "his shoe," actually, I just said it, /hiz shoo/, but in running text, I would just say /hishoo/, right?

Ammon Shea: Mm-hmm (affirmative).

Emily Brewster: The S is gone. It becomes a /sh/ sound instead of a /z/ and a /sh/.

Emily Brewster: So that's this process of assimilation, and that is what's happening in the pronunciation "excetera"; it's a more natural thing for our mouths to do. There are no words in either French or English that begin with "et," except for et cetera.

Peter Sokolowski: Oh, that's fascinating.

Emily Brewster: But "ex" is a very common way to begin a word, right? We've got exciting, exception, except. Some of the most common words that we use start with an "ex."

Peter Sokolowski: It reminds me of the nuclear/nucluar problem, where there is a common pattern like molecular, cochlear is a little less common, but molecular, which has this scientific connotation, like the word nuclear does, but there are very few words that actually have that pattern.

Emily Brewster: Right.

Emily Brewster: Now, it's not that that one is so hard to say. We can say the word likelier, for example.

Peter Sokolowski: Sure, sure, sure, sure.

Emily Brewster: We can do that "klee-er," but nuclear is this technical scientific term, like you say, and there are all these other scientific terms that have this "-ular" ending that sort of draws a word like nuclear to be "nu-cu-lar."

Peter Sokolowski: For these nonstandard pronunciations, I sometimes call it like the pull of gravity. You're attracted like a magnet to something that you've heard before.

Peter Sokolowski: Something that comes to mind is remuneration, which has to do with money and the amount of money that's being paid. And so we want to see maybe that word number or numeral. So you often hear it as "renumeration." In a way, there's a logic to that. It's just not what the word is.

Emily Brewster: Right. Yeah.

Ammon Shea: Yeah, remuneration still feels quite foreign, but to be honest, most words in English still feel foreign to me as my native language. So that's not so surprising.

Emily Brewster: We have talked about folk etymologies before. A folk etymology is when a word is actually shifted in its form to become something more logical or more familiar.

Ammon Shea: Absolutely.

Emily Brewster: And that's definitely what is happening when you're talking about "renumeration."

Emily Brewster: The word chaise longue. There's an alternate chaise lounge, and it's because longue, L-O-N-G-U-E, in English, is not really very meaningful, but lounge certainly is, especially when you're thinking about a particular kind of chair.

Peter Sokolowski: And it looks like it's for lounging, and we have a verb that kind of contributes to that. Chaise lounge, we've certainly talked about it and written about it. And there are a bunch of these; hangnail is one of them.

Peter Sokolowski: We ascribe a logic or we, post facto, apply a logic to this spelling of these words.

Peter Sokolowski: And this is a long way of saying that someone might be technically wrong with "excetera," for example, and it might get under your skin, it might bug you, but there's often a kind of logic behind these very common so-called errors, these nonstandard approaches to phonetics and to spelling.

Emily Brewster: The E-C-T spelling, which is one of the things that Michael was really objecting to, he's noticing this increase in the use of this spelling; and we do not yet include that in our dictionaries, E-C-T as a variant spelling of the abbreviation for et cetera; but F. Scott Fitzgerald apparently used it in his writing.

Peter Sokolowski: No kidding.

Emily Brewster: Yeah.

Ammon Shea: Published or unpublished?

Emily Brewster: These were in letters.

Ammon Shea: Yeah.

Emily Brewster: Sorry, not in his published writing, except that it just means no editor was correcting him, right? It may be all throughout The Great Gatsby.

Ammon Shea: I've noticed that there are a number of cases that have come up. Quite often, it's in the letters of F. Scott Fitzgerald.

Ammon Shea: So I think he had a relaxed grasp on certain usage conventions that people hold very important today.

Emily Brewster: Right. A relaxed grasp on usage conventions. Yes, I like that.

Ammon Shea: Yeah.

Emily Brewster: But he clearly had mastery of the language. He is a very highly regarded writer for good reason. He knew how to use words to communicate very well.

Ammon Shea: It just goes to show that you can write in what many people would consider to be substandard variants of English and still die a miserable alcoholic death.

Emily Brewster: But be read in high schools around the country.

Ammon Shea: Yes. Yeah, yeah, yeah. That too.

Emily Brewster: There's another word that this thinking about et cetera made me think about, and that is the word expresso.

Emily Brewster: Now, expresso, E-X-P-R-E-S-S-O, is included in our dictionaries with the same definition as espresso, E-S-P-R-E-S-S-O. So in this case, we actually include that spelling with the "ex." It has a pronunciation that matches it, "ex-pres-so," and it's considered less common, but not nonstandard.

Peter Sokolowski: So that means it's frequent enough.

Emily Brewster: And our evidence of both really starts to become significant in the 1950s, but they're both kind of bubbling up around the same time.

Peter Sokolowski: Another one like this that you might think is an error is the word aluminium, which is really just the British way of saying aluminum, but we enter it at its own spelling and we simply call it British. Although it may be like with remuneration and renumeration. Some people think, "Ah, you're adding an extra syllable to this word."

Peter Sokolowski: What was that other one where you add a syllable?

Emily Brewster: Is it mischievious?

Ammon Shea: Mischievious?

Peter Sokolowski: Yes. Yes.

Emily Brewster: I love mischievious. We include the variant pronunciation "mis-chiev-i-ous" and we enter it as nonstandard, but we don't include the spelling that kind of backs it up.

Emily Brewster: I'm not sure how I feel about that. If I'm going to say "mischievious," I'm going to spell it with an -ious.

Ammon Shea: I got to say, I always thought that mischievious was itself a more mischievious form of the word than mischievous was. It's an exemplary of itself. And so I think it deserves its own place based on that.

Emily Brewster: Yeah. Well, it's often used humorously and it's got this kind of playful nod to the word devious in it.

Peter Sokolowski: Is it possible that British English speakers use that more frequently? It may be just my ears that I've caught it more frequently, but it's a fun variation. And especially because of that "devious" harmonization that just brings this other idea kind of more actively into this word.

Peter Sokolowski: But clearly, we're just having fun with these words. And I think that notion of nonstandard, it's important to remember that's a usage label, and that usage in this case is what I call "the manners of language." In other words, it's sort of there to help guide you to not embarrass yourself and not offend others.

Peter Sokolowski: And it's true that you might be judged harshly if, in professional writing or in a school paper, that you present one of these spellings or pronunciations. You might be judged harshly by people who don't know you, for example.

Peter Sokolowski: And we do find it comfortable to judge other people by their spelling. It happens all the time on Twitter. So that's why I call it manners. It really doesn't have to do with the word itself. It has to do with how the word is situated in the culture of understood standard spelling and publishing.

Ammon Shea: I think that's a really great analogy, Peter. And if I could pursue it a little more, I think one of the things that's particularly useful about that is that, just as with manners, there are degrees of usage that you may wish to adhere to.

Ammon Shea: In many cases, the question involved is roughly analogous to, "Have you used the correct fork for the salad?"

Peter Sokolowski: Yep.

Ammon Shea: And in other cases, the question is more like, "Did you remember to put on pants before you left the house today?"

Ammon Shea: These are both, in some broad sense, a question of manners, but some are more important than other ones. I think it's important, and it kind of behooves us all, to not confuse the salad fork with the wearing of garments when we leave the house.

Peter Sokolowski: Perfect.

Emily Brewster: Here, here.

Emily Brewster: You're listening to Word Matters. I'm Emily Brewster.

Emily Brewster: Coming up, we explain inexplicable, or try.

Emily Brewster: Word Matters is produced by Merriam-Webster in collaboration with New England Public Media.

Peter Sokolowski: Word Matters listeners get 25% off all dictionaries and books at shop.merriam-webster.com by using the promo code MATTERS at checkout. That's MATTERS, M-A-T-T-E-R-S, at shop.merriam-webster.com.

Ammon Shea: I'm Ammon Shea. Do you have a question about the origin, history or meaning of a word? Email us at wordmatters@m-w.com.

Peter Sokolowski: I'm Peter Sokolowski. Join me every day for The Word of the Day, a brief look at the history and definition of one word, available at merriam-webster.com, or wherever you get your podcasts.

Peter Sokolowski: And for more podcasts from New England Public Media, visit the NEPM Podcast Hub at nepm.org.

Emily Brewster: Given a matter that cannot be explained, English speakers are far more likely to describe the matter as "inexplicable" than they are to describe it as "unexplainable." But why? Peter will try to explain.

Peter Sokolowski: We always seek logic in language. And one of the intriguing characteristics about English is that we often have a lot of words for kind of the same thing, and that isn't always logical when you think about it. That means they overlap, that means we have synonyms, of course, and that means also that we have registers or colors, sort of sophisticated designations, of denotation and connotation.

Peter Sokolowski: And that's what we're here for. I mean, that's what the dictionary does. But for example, we don't make a big deal about the differences between words like trusty and trusted. We use them both; "my trusty knife," "a trusted friend."

Peter Sokolowski: But if someone were learning English, they would have to learn that particular sub-pattern of adjectives.

Peter Sokolowski: And think of, in English, the fact that for something that is big, we have so many synonyms. We have huge and large and great and enormous and gargantuan and humongous and gigantic and ginormous. There's so many of these things.

Peter Sokolowski: And that's just sort of the curious thing. I've always wondered why we have so many words for big things in English and not pairs of them for small things.

Peter Sokolowski: And one of these pairs that overlaps is unexplainable and inexplicable, which, weirdly enough, are semantically almost identical, aren't they? I mean, they sort of mean the same thing; "not able to be explained."

Emily Brewster: Right. Trusty and trusted, I would use in different contexts, but ... Let's see, "This distinction is unexplainable, it's inexplicable"; I think those basically mean the same thing.

Peter Sokolowski: Yeah. I think semantically, at least for the definition, it'd be hard to make a distinction.

Ammon Shea: I think inexplicable is paired with the strong possibility of blame in many cases.

Peter Sokolowski: Oh, interesting.

Ammon Shea: You would say, "The inexplicable decision you made to invite your brother this weekend." That makes sense. You wouldn't say, "The unexplainable decision you made to invite your brother." It's "inexplicable" why you would do that, not "unexplainable."

Emily Brewster: I think I would say unexplainable.

Ammon Shea: I feel like inexplicable, at least in my idiolect, is paired with the soon forthcoming blame on some matter.

Emily Brewster: So is unexplainable, maybe that's a little more gentle.

Ammon Shea: That's self-referential. It's unexplainable why I did something, but it's inexplicable why you did something.

Peter Sokolowski: Hmm. Ah.

Ammon Shea: That's the distinction for me.

Peter Sokolowski: Well, there's a kind of a neutral quality, is what you're saying, to unexplainable, which actually may be right. That's an interesting color.

Peter Sokolowski: This is one of the things about English in particular, which is that English often has pairs of nearly synonymous words. Usually one has derived from Old English and one has derived from Latin or French.

Peter Sokolowski: Think about doable and feasible, or many and numerous, or friendly and amicable. None of those are completely a hundred percent overlapping in usage, but we all kind of squint and see, "Oh yeah, they kind of mean the same thing."

Peter Sokolowski: This case is a little different, because inexplicable and unexplainable both have Latin roots and they still occupy the same lexical space. So this is kind of an interesting thing. In other words, they grew up next to each other in parallel in the English language after the 13th century, you know, when these words kind of came into the language.

Emily Brewster: But they don't have the same Latin root.

Peter Sokolowski: No. Right, exactly.

Peter Sokolowski: So explain comes ultimately from planus or planus, which means "flat." In French, the word for map is still plan, P-L-A-N. Plan. And we do use the word plan. In some sense, you could say that plan is this ultimately figurative use of what was a piece of paper on the table that you were looking at, a literal plan, which was a map; a plan to go to the movies tonight was really kind of a map for your evening, right?

Peter Sokolowski: So there is something to that, but the Latin word planus, meaning "flat," or the verb related to it, which meant "to make flat" or "to make level," which meant "to make plain, to make clear, to make understandable."

Emily Brewster: It was figurative even-

Peter Sokolowski: In Latin.

Emily Brewster: ... In Latin then.

Emily Brewster: And English, of course, has the word plane, right? P-L-A-N-E.

Peter Sokolowski: And it comes from the same root. And it's also the tool, plane, that makes something flat for a carpenter.

Peter Sokolowski: So that's an interesting root that has a lot of derivations in English, but explicable, or explicate is the verb, comes from a different root, explicare. That's the verb that means literally "to unfold," which is also a figurative way to say "to make something clear," or "to make something easy to understand." You unfold it, and, "Oh, now I see the whole picture." And that gives you the reason or the cause for something.

Peter Sokolowski: And this is the same root that gives us words like complicit or implicit or explicit. And when you think about the roots, complicit means "folded together", implicit means "folded in," and explicit means "unfolded" or "folded out."

Peter Sokolowski: So it's kind of an interesting etymological journey that you can take through these words.

Emily Brewster: So explain is "laid out flat" and explicable is "unfolded."

Peter Sokolowski: Yes. Unfolded in order to see all of it, in order to make clear.

Peter Sokolowski: So the word complicate has that plic in there, the same as explicate, and complicate means "to fold together."

Peter Sokolowski: So if you're complicit, you're folded in with your co-conspirators, but if you complicate something, that's also folded something together. That's too many things together.

Peter Sokolowski: It's just an interesting way that we use this plicare root. This is the ply word in English, like plywood, which has layers or levels or folds that you put together.

Peter Sokolowski: So that's where all of those things come from.

Peter Sokolowski: So we have these two words that have two different roots, both of which had a figurative use that meant "to make clear." And that's kind of interesting.

Emily Brewster: Yeah.

Peter Sokolowski: And that's only in the positive though. We're talking about explainable and explicable.

Ammon Shea: Plicare can give rise to another very, very obscure word, which I think is only in the OED, which is inexplicant, I-N-E-X-P-L-I-C-A-N-T, which, unfortunately, I have to say means just "giving no explanation." And I thought it would be nice if inexplicant referred to a person who could not be explained, kind of like a supplicant is a person who supplicates. Inexplicant to me feels like it should mean an inexplainable person, but it doesn't.

Emily Brewster: It could also mean a person who refuses to explain.

Ammon Shea: Even better.

Emily Brewster: I like them both. We can do what we can.

Peter Sokolowski: I think that sounds like the kind of word that was used by someone who is used to working in Latin or translating from Latin, like a scientist or a lawyer or a scholar of the 16th or 17th century. That sounds like a word that was sort of coined in English, but is really a Latin word. Does that make sense?

Ammon Shea: That is entirely explicable.

Peter Sokolowski: So then we have these positive terms, explainable and explicable. They're both found in print in 13th, 14th century.

Peter Sokolowski: What's harder to explain is that their predictable negations, so unexplainable and inexplicable, show wildly different usage patterns from the verbs that they were derived from.

Peter Sokolowski: So to begin with, explain is much more commonly used than explicate in English; "Let me explain this to you," or, "Can you explain why you were late today?" You know, that kind of thing. You would explain the rules of baseball, but you would explicate scripture, for example, or explicate a text.

Peter Sokolowski: In French, it's [foreign language 00:19:16], is the classical high school essay in which you illuminate your thoughts regarding something on the page. And it's that word explicate; "unfold your knowledge," basically.

Peter Sokolowski: But explicate is so specific and technical compared to explain.

Emily Brewster: Right. You would never, for example, explicate why you invited your brother for the weekend.

Peter Sokolowski: Right. But the fact that we use explain much more frequently than we use explicate, I believe, and this is just a theory, is why we attach un- to explain, because un- is the Old English form of the negation; in- would be the Latin form.

Peter Sokolowski: And so the reason we say "unexplainable"—so we have a Latin base with an Old English prefix—is because this word has essentially been anglicized or nativized by its very frequency. Because it's so common to use this word in English, it becomes comfortable like an old shoe and you put it in with the Old English prefix.

Peter Sokolowski: I think it's an interesting criss-cross of derivations. You say "unexplainable" because the word is so comfortable in English.

Emily Brewster: I like that theory.

Ammon Shea: I like that definition. I'm going to propose that under un- we now revise that to "the comfortable old shoe of negation."

Peter Sokolowski: Well, there is something comfortable about these Old English terms. They tend to be the terms that we associate with hearth and home and with family. And of course, they're the function verbs of English, like make and do. They're all our swear words that, if you burn your finger on the stove, that's what you're going to utter. They're the comfortable words, and the words for members of the family, and words like girl ... They just tend to be the homey words.

Peter Sokolowski: And so they are more comfortable in that sense, but explicate, explicable uses in-, I-N, inexplicable, which is that Latin prefix.

Peter Sokolowski: The people who were writing in these times, we're talking about the 1400s, these were people who were almost certainly fluent in Latin themselves. They would've written Latin for scientific or legal reasons or bureaucratic reasons. And so they would've said, "Oh, well, this is the correct prefix for this word." It's very easily explainable.

Emily Brewster: The in- would've gone naturally with something from explicare.

Peter Sokolowski: Yes. And they would've known that.

Peter Sokolowski: So then what we get is to measure which of these is used more frequently today. And I just used a very common corpus, one of our favorite corpora, that's the plural of corpus, The billion word Corpus of Contemporary American English, just to take a look. And basically, explicable and explainable are used almost on par with each other in professionally edited prose.

Peter Sokolowski: That doesn't mean around the house that you would say explicable as often as explainable, you probably wouldn't, but if you think about what a corpus is, it's often a lot of newspaper articles, often about government or international affairs or finance, and so it tends to be a more formal register of language anyway.

Peter Sokolowski: So we find these two words to be roughly on par, but interestingly, unexplainable is used about twice as often as the positive explainable. But the real interesting thing is that inexplicable is used about 10 times as often as explicable or explainable is. And so what we find is, for whatever reason, English speakers really like this negative formation.

Emily Brewster: Inexplicable.

Peter Sokolowski: Inexplicable. It's far and away, in terms of published prose, the more common form.

Emily Brewster: Let me just clarify. You said that unexplainable is also more common than explainable, but inexplicable is way more common than unexplainable or explicable.

Peter Sokolowski: Yes, exactly. So for whatever reason, we like the negative forms of these words.

Peter Sokolowski: And maybe there's a good reason for that. If you're writing something and it's edited and is published, you've thought it through, and "unexplainable" or "inexplicable", these are really good reasons. These are sort [inaudible 00:22:49] of arguments, aren't they? These are why you are writing about this subject in the first place maybe, is that it's hard to understand.

Peter Sokolowski: And so the fact that inexplicable, however, so far exceeds all of these other forms in print, is itself a bit of a mystery. I mean, there's no real logic to this. It's just the way it is.

Peter Sokolowski: Now, there are other negative terms that are far more common than their positive peers. So a word like ineffable or a word like irreconcilable or inextricable or irrevocable or unfathomable. You realize that we do have a kind of habit of using the negatives of these long kind of Latin words more frequently than their positives.

Emily Brewster: Well, in some ways, I think it's because that's where the more interesting idea is. If something is effable, it's just understandable, right? You can talk about it. And that's not really interesting because most things are effable. So the interesting thing is the thing that is ineffable.

Peter Sokolowski: Exactly.

Emily Brewster: And also with unexplainable and inexplicable.

Ammon Shea: Maybe it's kind of like the way that we only define things or label things as substandard or nonstandard now. And if it's standard, it's not worthy of designation, and if it's explainable, we don't need to take note of that; only if it's lacking the ability to be explained are explicated.

Peter Sokolowski: We sometimes say this term, "hiding in plain sight." If something is effable, you've said it, or you have the capacity to say it easily. There's no reason to draw attention to the manner in which you say it, for example. But ineffable, boy, that is a word that opens up all kinds of interesting ideas. And it's true that this is why language exists; to argue and explain.

Peter Sokolowski: And so maybe that is the explanation of the fact that inexplicable is a little bit, surprisingly, the most common form of all of these terms.

Ammon Shea: There's a lovely, old obscure word, which I don't know even if anybody's defining it these days, which was infandis, which was, I think, defined as "too odious to be spoken of, unfit for speech." And I've seen it only in a few places, but I'm also fairly certain I've never seen fandis, the positive form of it, because why bother? If it's not too odious to speak of, then there's no need.

Emily Brewster: These explanations are entirely fathomable.

Emily Brewster: Let us know what you think about Word Matters. Review us wherever you get your podcasts, or email us at wordmatters@m-w.com.

Emily Brewster: You can also visit us at nepm.org. And for the Word of the Day and all your general dictionary needs, visit merriam-webster.com.

Emily Brewster: Our theme music is by Tobias Voight. Artwork by Annie Jacobson. Word Matters is produced by John Voci.

Emily Brewster: For Ammon Shea and Peter Sokolowski, I'm Emily Brewster.

Emily Brewster: Word Matters is produced by Merriam-Webster in collaboration with New England Public Media.