...Head Bobbing

Needful has two primary meanings in the English of the modern era: “needed or necessary,” and “being in need.” Each of these senses has been in regular use in our language for close to a thousand years, with considerable evidence from many of our most respected writers; it is unclear to us what resemblance it has to the bobbing of heads. In a vain attempt to make up for our ignorance in this regard we offer you the only word we know of that does in fact relate to a bobbing head, which is nod-crafty. This word is enormously obscure, having apparently only been used by Francis Bacon; the sole dictionary that includes it, the Oxford English Dictionary, defines it as “given to nodding the head with an air of great wisdom.”

...a Labradoodle

A labradoodle is a breed of dog, a cross between a Labrador retriever and a poodle. It is not a terribly old breed, and came into existence as the direct result of dog breeders mixing two distinct, existing breeds. Ideation (“the capacity for or the act of forming or entertaining ideas”) is not a terribly new word, having been in regular use in English for approximately 200 years (our earliest record of use comes from the poet Samuel Taylor Coleridge in 1818). It is formed by combining an older word, ideate, with the suffix –ion. You are well within your rights to dislike the word, but it does not much resemble the labradoodle, in either heritage or appearance.

...the Fall of Rome

The question of where one should put one’s apostrophe is a vexatious one for many people, and clarity on this issue is difficult to come by, as the rules regarding the use of this piece of punctuation are constantly changing. The apostrophe’s shift does have some similarity to the decline of the Roman Empire: both events took hundreds of years to unfold (and in the case of the apostrophe, the process of change is still ongoing).

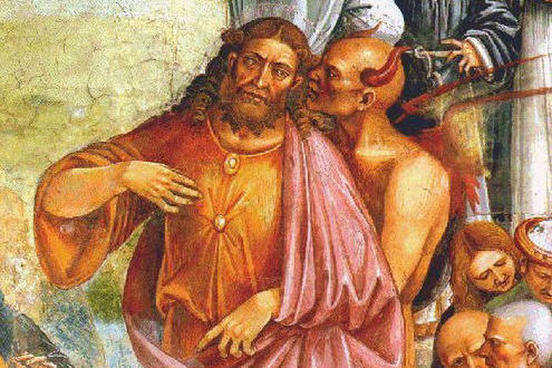

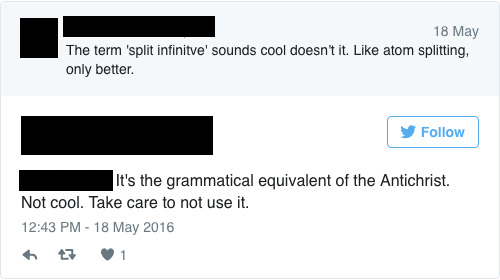

...the Antichrist

Merriam-Webster has no position on the Antichrist, except insofar as it is a word for which we provide a definition. We cannot give you any information as to whether this entity is real or imaginary, or thoughts on the correct mode of address should you meet the Antichrist. We can however, inform you that split infinitives (“an English phrase in which an adverb or other word is placed between to and a verb”) are very real indeed, and some people do not care for them. They have been a part of the English language since at least the 14th century, and are much more accepted in use today than they were a few decades ago.

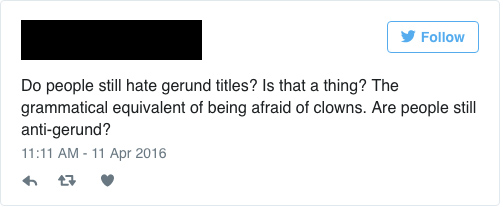

...Fear of Clowns

Before addressing the issue of whether people are still anti-gerund, we should point out that the English language, in its bountiful glory, has a word for prickling sense of terror that comes over some people when they encounter a person with face paint and a red nose. That word is coulrophobia, and we define it as “abnormal fear of clowns.”

As for the gerund (“an English noun formed from a verb by adding –ing”), yes, there are some people who very much hate them.

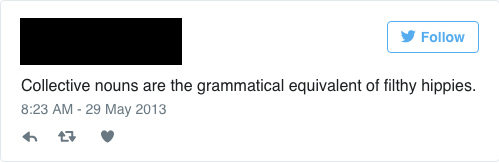

...Dirty Hippies

Collective nouns (“a noun such as ‘team’ or ‘flock’ that refers to a group of people or things”) are beloved by many connoisseurs of language, although it must be confessed that some lexicographers find them tiring, as most collective nouns are not in actual use, but are instead employed as examples of their class ("did you know that the word for a group of larks is an exaltation?").

The heyday of the collective noun was between the 15th and 17th centuries, when fanciful lists of them were often put into glossaries of hunting and hawking. Juliana Berners’ 1556 work, The Booke of Hauking, Huntyng and Fysshyng, contains the following examples: a superfluity of nuns, an eloquence of lawyers, and a doctrine of doctors.

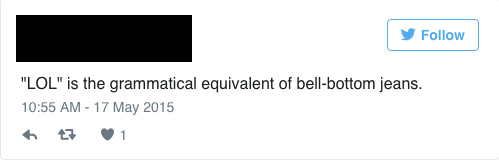

...Bell-Bottoms

The oft-maligned style of pants known as bell-bottoms does have something in common with many of the abbreviations encountered in various forms of social media and in Internet chat rooms; both have been in use for longer than many people think. We have been describing pants with a distinct flare at the lower portion as being bell-bottomed since the ‘70s…um, the 1870s.

The sailor is surely an honest fellow, in bell-bottomed trousers, and a straw hat with a blue ribbon around it, while the Captain, to his mind’s eye, is a hale and hearty individual, dressed in blue, and forever standing on the quarter deck with a six-foot spy-glass to his eye, and hailing “ship, ahoy!” The Brooklyn Daily Eagle (Brooklyn, NY), 24 Sept. 1873

LOL is not nearly as old as that, although the earliest known evidence still comes from before the Internet was ostensibly warping the minds of our youth; we have been annoying people with this abbreviation since 1989. Other forms of Internet slang have been with us for quite a bit longer; OMG, for instance, has been found in a letter written to Winston Churchill in 1917.

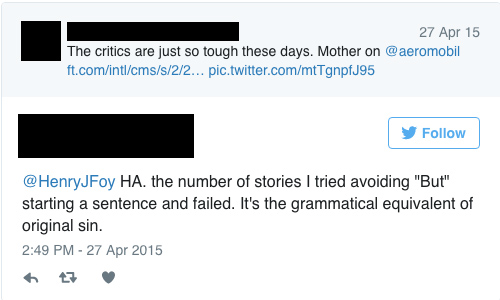

...Original Sin

If you ever have doubts about whether it is permissible to begin a sentence with and or but you need look no further than that slim volume which has been both causing and settling arguments on the subject of English usage since the middle of the 20th century, Strunk and White’s The Elements of Style. No, they don’t address the issue directly, but they do use each one of these words to begin a sentence, one right after the other.

But since writing is communication, clarity can only be a virtue. And although there is no substitute for merit in writing, clarity comes closest to being one.

—William Strunk Jr. & E. B. White, The Elements of Style, 1959

There is nothing wrong with beginning a sentence with but or and. And the only thing that connects this use to the subject of original sin is the Bible; most early English versions of that work have dozens, if not hundreds of sentences that begin with one of these two words.

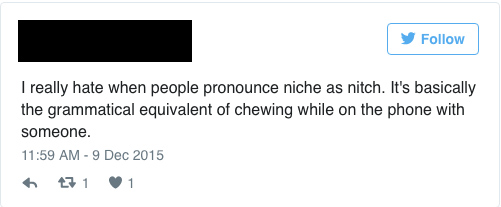

...Chewing on the Phone

Whether you pronounce the word niche as something that rhymes with “ditch,” “dish,” or “yeesh,” you have nothing to worry about. First of all, it is not the grammatical equivalent of anything; grammar and pronunciation are two separate fields. Furthermore, we give all three of the pronunciations listed above as acceptable ways of saying this word.

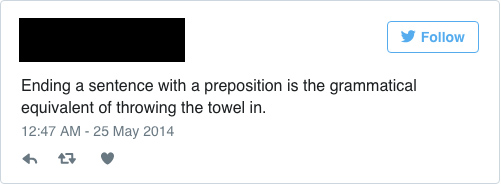

...Throwing in the Towel

People have been complaining about ending sentences with prepositions for a very long time. In fact, by the time we began using the expression throw in the towel (early 20th century) the notion that sentences should not end with a preposition was already more than 250 years old (it was cautioned against in the middle of the 17th century). You would think, after having been scolded for putting to, through, or with just before a period for more than 350 years, the English-speaking people would finally get their act together, but this has not been the case. Why is this? Probably because our language very easily accommodates sentence-final prepositions, and people like to use them. Almost all usage guides have, for over a century, agreed that they are acceptable to us, and while there may not be applause for ending a sentence with a preposition, there is really nothing wrong with it.