What to KnowThe plural of elf is elves. While elfs appears occasionally in edited prose, it is widely considered incorrect. To help remember the correct spelling, try remembering the plural forms of words like shelf and leaf, as in “a group of elves wearing scarves is hiding under the leaves.”

The mischievous creature known as the elf seems to turn up in all kinds of narrative universes—from the Brothers Grimm to Middle Earth to Harry Potter. Such creatures also turn up in advertising, where they are known for, among other things, making cookies inside a tree. And of course, Santa Claus relies on a workforce of these tiny individuals to make the toys he delivers to children every December.

Since these creatures usually work as a team (a necessity, given how relatively tiny they are), it’s important to know how to render the plural for their species.

The appearance of elves in Christmas narratives became prominent in the United States in the 19th century.

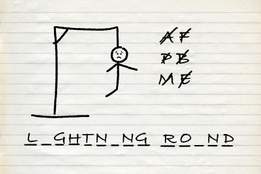

Modern use of the word elf almost always shows up in the plural as elves, with the spelling elfs turning up on infrequent occasions:

Size doesn’t matter much in the world of elves. It’s personal growth that makes all the difference, according to the highly entertaining production of “Elf – The Musical” now running at the Lyric Music Theater in South Portland.

— The Portland Press Herald, 9 Dec. 2019Based on the classic by J.R.R. Tolkien, “The Hobbit Play” will feature 44 M.V. Charter School students … there will be singing dwarves, dancing hobbits, and elves, along with other characters—Gollum, trolls, goblins, and even a dragon.

— The M.V. Times (Martha’s Vineyard, Mass.), 10 May 2019Santa will fly in with two of his elfs, and Santa’s chair will be propped up so children can see Santa.

— The Edmond Sun (Oklahoma), 14 Dec. 2018

The Origin of 'Elves'

Elf derives from Old English. In the epic poem Beowulf, which dates to around the 10th century, elves (rendered as ylfe) are among a “woeful breed” of creatures descended from the biblical son Cain. In Germanic folklore, the term elf referred to any of a variety of creatures, usually of small stature, not necessarily out to cause harm but always mischievous. At various times, elves were believed to cause illness in humans or cattle; to cause people to have bad dreams by sitting upon them while they slept; or to swoop in and steal young children, replacing them with changelings.

Elves were a ripe subject for poets ranging from Chaucer to Shakespeare to Dryden, though no consensus could seem to be reached on how to render the plural. That might have been due partly to popular perception of elves as distinctly belonging to past times, leading to a scarcity of the word’s occurrence in then-contemporary prose. The second edition of the Encyclopædia Britannica (1777–84) calls the word elf “obsolete” but reports that belief in such creatures “still subsists in many parts of our own country. . . In the Highlands of Scotland, new-born children are watched till the christening is over, lest they should be stolen or changed by some of these phantastical existences.”

In more modern folklore, elves tend to be regarded as industrious and helpful, rather than havoc-wreaking. The story now best known as “The Elves and the Shoemaker,” in which the creatures work during the night to help an indigent merchant, was published in the German Grimm’s Fairy Tales as “Die Wichtelmänner”; Margaret Hunt chose “The Elves” as the title when the story was translated into English in 1884.

Elves and Christmas

The appearance of elves in Christmas narratives became prominent in the United States in the 19th century. Clement Clarke Moore’s 1823 poem “A Visit from St. Nicholas” describes the visitor as “a right jolly old elf.” In 1850, Louisa May Alcott completed a manuscript entitled Christmas Elves, but it was never published. A poem called “The Wonders of Santa Claus,” published by Harper’s Weekly in 1857, describes the legend: “In his house upon the top of a hill, / And almost out of sight, / He keeps a great many elves at work, / All working with all their might.” An American women’s magazine called Godey’s Lady’s Book is credited with one of the earliest depictions of elves as toy workers assisting Santa, with workshop illustrations adorning the cover of its 1873 Christmas issue.

Similar Plurals to Elves

By then, use of elves as the preferred plural for the creature was well established in English, following the example set by many other nouns that end in an –f that converts to a v when the noun in pluralized: shelf becomes shelves; scarf (usually) becomes scarves; wolf and calf becomes wolves and calves. We speak of the leaves on the trees, a den of thieves, two halves making a whole. Then there are those nouns that end in –fe: wife and knife become wives and knives.

Spelling, in this case, is determined by phonetics. The voiceless \f\ sound that ends these words became a voiced \v\ simply by habit of speech when the word in question was pluralized. This rule doesn’t apply to all such nouns, however. Serf, for example, gets pluralized with a standard –s: serfs. Chief, despite ending in the same three letters as thief, gets pluralized as chiefs. Same with briefs, beliefs, roofs, and reliefs, as well as just about all words ending in double-f: tariffs, bailiffs, sheriffs, cliffs, mastiffs, bluffs, cuffs, earmuffs.

Elves and Dwarves (or Dwarfs?)

A noun comparable to elf that went its own route when it came to establishing a plural is dwarf. While both dwarfs and dwarves have demonstrated historical use for the noun (which, like elf, derives from Old English), the preference for dwarfs was perhaps encouraged by the title of Disney’s 1937 animated film Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs.

But the popular fantasy writer J. R. R. Tolkien preferred the plural form dwarves in his works, possibly as a deliberate echo of elves:

As they sang the hobbit felt the love of beautiful things made by hands and by cunning and by magic moving through him, a fierce and jealous love, the desire of the hearts of dwarves.

— J.R.R. Tolkien, The Hobbit, 1937

In a foreword to The Hobbit, Tolkien acknowledged that dwarfs was the “only correct plural” of dwarf, but that he had opted for dwarves “only when speaking of the ancient people to whom Thorin Oakenshield and his companions belonged.”