It's/Its/Its'

Your gown shall be unpicked, but I do not remember its' being settled so before.

—Jane Austen, letter to Cassandra Austen, 7 October 1808

Many struggle with it’s vs. its (and some of us even find occasion to wrangle in an occasional its’). If you are one such person, take comfort in the fact that Jane Austen was likewise befuddled—although she at least had the excuse that the rules governing this matter were not yet entirely set.

A quick refresher: it’s is used when the writer intends to provide a shortened form of "it is" ("it’s a shame"); its is used when indicating possession ("the museum is failing, as its membership is declining"); its’ is generally avoided.

A look at Austen’s correspondence shows that she paid very little attention to the difference between these forms of the word. In an 1814 letter to her older sister, Cassandra, Austen wrote "It may take it’s chance"; in an 1808 letter, she used the correct "Our evening was equally enjoyable in its way."

No matter which version of this mistake one makes, there will be at least one authority from the past several hundred years of English who would have found it correct. The exception is James Buchanan, the author of A Regular English Syntax, who in 1767 declared "It’s for it is is vulgar; ‘tis is used."

Most Best

Shee has the most best, true, feminine wit in Rome!

—Ben Jonson, The Workes of Ben Jonson, 1616

The double superlative doesn’t get as much attention as the double negative, but it's still considered an error. Yet as we see from this quote by the famous 17th-century writer Ben Jonson, such was not always the case. A few hundred years ago, it was common to precede an –est word with a most; the most notable example may be found in Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar, when Antony says "This was the most unkindest cut of all." Shakespeare was fond of the double superlative, and occasionally used it twice in the same line—as in King Lear, when the King of France says "the argument of your praise, balm of your age, most best, most dearest. . . ."

These days, you'd do well to avoid it. The double superlative has been out of style for a long time: when Alexander Pope edited an edition of Shakespeare's work in 1725, he changed Antony's line to "This, this, was the unkindest cut of all."

Internecine

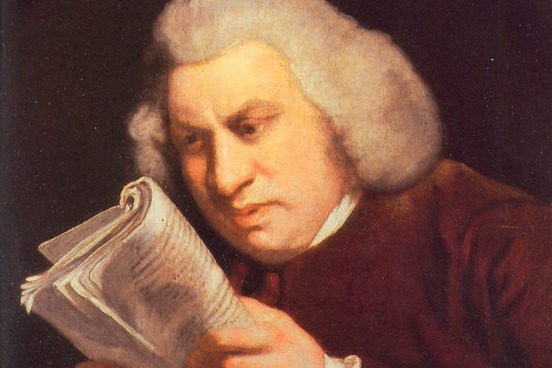

Internecine, adj. (internecinus, Latin) Endeavouring mutual destruction.

—Samuel Johnson, A Dictionary of the English Language, 1755

Samuel Johnson is rightfully remembered today as one of the true giants of English lexicography. His 1755 dictionary was a masterpiece of defining and organization. It also was responsible for the current sense of the word internecine, through a mistake on Johnson’s part.

Prior to Johnson this word had a singular meaning: "marked by great slaughter." However, the great lexicographer mistakenly supposed that the prefix of inter- carried the meaning of "mutual" or "reciprocal," and so defined the word as meaning "mutual destruction." Although inter- often has this meaning, it did not in this case. However, enough subsequent dictionaries copied from Johnson that the new definition of this word took on the sense of "mutual," which is its most common sense today.

Between You and I

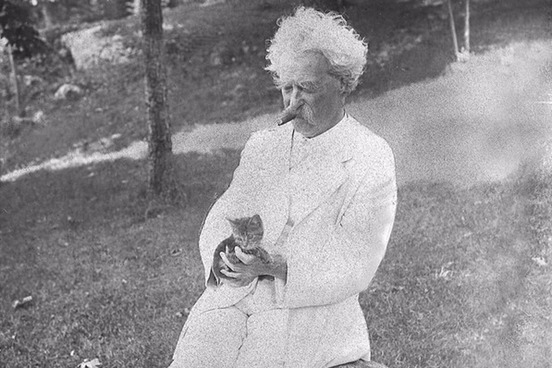

Now between you and I, Billy, I set that dog “Kurney” down for a bloodthirsty desperado, the first time I ever looked into his vindictive countenance.

—Mark Twain, Letter to William H Clagett, 28 February 1862

As is so often the case with supposed grammatical errors, the best known instance of the widely shunned phrase "between you and I" comes from the writing of William Shakespeare. In The Merchant of Venice, he wrote "All debts are cleared between you and I." Yet this error (it is judged improper since I follows a preposition, between, and so should take the objective case of me) may be found in the writing of a great number of other esteemed authors.

Between you and I, I think him as odd, queer a fellow as you can do for your life.

—Henry Fielding, An Old Man Taught Wisdom, 1735Betweene you and I Sir, we doe but make show.

—Ben Jonson, Bartholmew Fayre, 1631Oh, Dolly! Between you and I, It’s as well for my peace that there’s nobody nigh.

—Thomas Moore, The Fudge Family in Paris, 1818

Rascalliest

Thou hast the most unsavoury similes and art indeed the most comparative, rascalliest, sweet young prince.

—William Shakespeare, Henry IV, Part One

There is a good deal of confusion surrounding which adjectives should be modified by the addition of an –er or an –est, and which should instead be modified by placing the words more or most in front. One thing we all seem to agree on, at least in this day and age, is that words of three syllables or more should not be have the –er or –est endings tacked on. It is jarring to our ear to hear that something is pretentiouser or unjustifiablest.

Once again, we may find Shakespeare flouting these rules (which were not yet rules at the time), and employing –ers and –ests on words that would make an English teacher wince.

And Benedick is not the unhopefullest husband that I know.

—Much Ado About NothingAnd so may I, blind fortune leading me, miss that which one unworthier may attain, and die with grieving.

—The Merchant of VeniceHe and Aufidius can no more atone than violentest contrariety.

—Coriolanus

Stupider

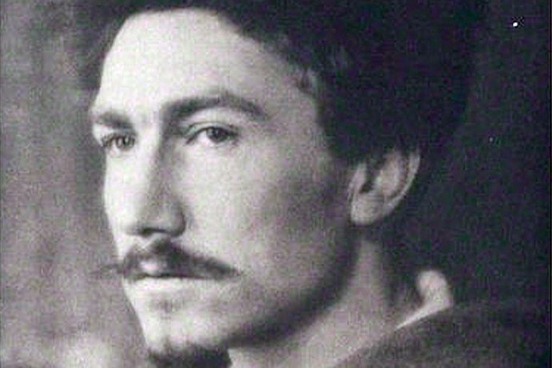

The life of Occidental mind fell apart into progressively stupider and still more stupid segregations.

—Ezra Pound, "Confucius and Mencius," Selected Prose, 1909-1965

While we’re on the tricky subject of which comparative adjectives in English should end in –er or –est, and which should instead be modified with more or most, let’s look at the curious case of stupid. Many people seem to be of the opinion that stupider is an abomination, and only used by the most stupid writers. It is unclear why this is so, as there are a number of similar words, such as solider, which, although used rarely, attract little opprobrium.

The general guidelines are that adjectives of one syllable are modified with –er or –est—except for exceptions, such as ill, good, and bad. Two-syllable adjectives that end with a vowel or a vowel sound, such as mellow, can be modified by –er and –est. Most two-syllable adjectives that end in a consonant will be modified instead with a more or a most.

Yet there are a number of two-syllable adjectives that end in a consonant which we are perfectly comfortable modifying with –er and –est. Pleasanter and pleasantest do not raise our hackles, so why does stupider? There is no good reason why this form has been found objectionable, but the fact remains that it is verboten to many people. It has seen limited use in English over the centuries, and the relative lack of evidence for it suggests that the word does sound a bit off to many writers, even if there was no clear rule prohibiting it. One writer who apparently never got the memo about stupider, however, is Ezra Pound, who used it extensively in his writing:

If you weren't stupider than a mud-duck you would know that every kick to bad writing is by that much a help for the good.

—Letter to William Carlos Williams, 11 Sept. 1920Pesanza for Possanza seems to me simply the duller, even stupider word, a dead instead of an active word.

—"Cavalcanti," Literary Essays of Ezra PoundDeath, insanity

suicide degeneration that is, just getting stupider as they get older

—"Canto LXXVI"

More Perfect

We the people of the United States, in order to form a more perfect union, establish justice, insure domestic tranquility, provide for the common defense, promote the general welfare, and secure the blessings of liberty to ourselves and our posterity, do ordain and establish this Constitution for the United States of America.

—Preamble to the United States Constitution, 1787

Most of us, whether we realize it or not, have been taught something of absolute adjectives. These are words which permit no variation of degree; something either is this adjective, or it is not, and there is no wiggle room. The subject has been given considerable attention over the years, as people who care very much about the state of our language have come to the defense of words such as perfect, unique, and supreme, on the grounds that they should not be modified.

Yet many writers over the years, including the authors of the United States Constitution, have seen fit to fudge many of these absolute adjectives.

This Gentleman, I say, has constructed an Air pump, by which we are impower’d to make Boyle’s Vacuum, much more perfect than heretofore.

—Benjamin Franklin, letter to Thomas Clap, 8 Nov., 1753You see that my primary object in the formation of treaties is to take the commerce of the states out of the hands of the states, and to place it under the superintendance of Congress, so far as the imperfect provisions of our constitution will admit, and until the states shall by new compact make them more perfect.

—Thomas Jefferson, letter to James Monroe, 17 June 1785If he is, he will inform you of the plan agreed upon between General Du Portail and myself, which he was instructed in the first place to carry into execution, afterwards to receive such additions and improvements, as might be found necessary to render the plan more perfect.

—George Washington, letter to Major General Alexander McDougall, 9 February 1779

All of these examples stand as useful reminders that language is constantly changing, and that no rules governing grammar or usage are ever set in stone—though your own writing will be more perfect if you avoid this phrase.