Butter

In his 1721 book An Universal Etymological English Dictionary, Nathan Bailey took a few shortcuts with his definitions. One striking example is his treatment of the word butter, which he glossed as “a Food well known.”

This was a not uncommon manner of defining common words at the time. Many of the earliest English dictionaries focused mainly on defining “hard words” and did not expend much effort on explaining the meaning of words that most people would be likely to know.

No one appears to have approached the levels of sloth in this regard that were reached by Benjamin Norton Defoe, who, in his 1735 A New English Dictionary, managed to define no fewer than 68 headwords as “well known.” Laugh and sneeze are both defined by Defoe simply as “an action well known”; bull, cow, horse, and ox are all defined as “a Beast well known”; and tree is given the simplest definition of all: “a thing well known.”

Pastern

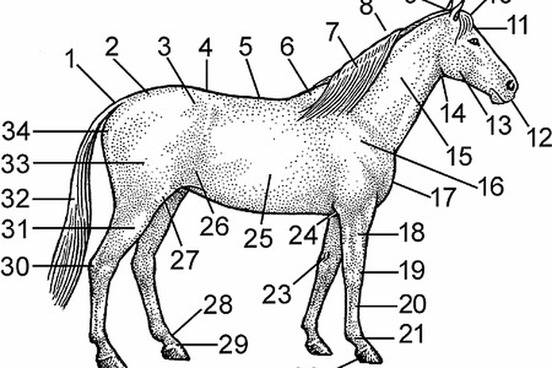

In Samuel Johnson’s great 1755 dictionary, the word pastern was defined as “the knee of a horse.” It's not. The actual meaning of the word is “a part of the foot of an equine extending from the fetlock to the top of the hoof."

When confronted with this error by a woman and asked how he had come to make such a mistake, Johnson was reported to have replied “Ignorance, madam, pure ignorance.”

In Johnson’s defense, he had essentially compiled his entire dictionary, which contained tens of thousands of headwords, by himself. We can excuse a few mistakes.

Elephant

It should be stated once again that Samuel Johnson was truly one of the giants of English lexicography, and a man who did more than perhaps any other in advancing the state of our dictionaries. That being said, we may still poke fun at him for some of his definitions, which tended on occasion to stray somewhat from strict adherence to fact.

Consider, for instance, his definition for elephant taken verbatim, and offered without further comment, from his 1755 dictionary:

"The largest of all quadrupeds, of whose sagacity, faithfulness, prudence, and even understanding, many surprising relations are given. This animal is not carnivorous, but feeds on hay, herbs, and all sorts of pulse; and it is said to be extremely long lifed. It is naturally very gentle; but when enraged, no creature is more terrible. He is supplied with a trunk, or long hollow cartilage, like a large trumpet, which hangs between his teeth, and serves him for hands: by one blow with his trunk he will kill a camel or a horse, and will raise a prodigious weight with it. His teeth are the ivory so well known in Europe, some of which have been seen as large as a man's thigh, and a fathom in length. Wild elephants are taken with the help of a female ready for the male: she is confined to a narrow place, round which pits are dug; and these being covered with a little earth scattered over hurdles, the male elephants easily fall into the snare. In copulation the female receives the male lying upon her back; and such is his pudicity, that he never covers the female so long as any one appears in sight."

Anatiferous

The 17th century lexicographer Thomas Blount mistakenly defined the word anatiferous as “that brings the disease or age of old women” in his 1656 dictionary, Glossographia. This was an understandable error for two reasons.

The first reason is that anas can refer in Latin to senility in women, or to disease in old women.

The second reason is that the actual definition of anatiferous is rather odd: it means “producing ducks or geese.”

Dog and Cat

Noah Webster is rightfully recognized, along with Samuel Johnson, as one of the towering figures of lexicography. His 1828 two-volume An American Dictionary of the English Language helped to establish the independence of the North American varietal of English.

However, before Webster published this work, he made a notably more modest preliminary effort at creating a dictionary. In his 1806 A Compendious Dictionary of the English Language, he defined both cat and dog with the exact same phrase: “a domestic animal.”

Two decades later, when Webster published his great dictionary of 1828, he took considerably more care with the definitions of these animals. Dog was defined as “A species of quadrupeds, belonging to the genus Canis, of many varieties, as the mastiff, the hound, the spaniel, the shepherd’s dog, the terrier, the harrier, the bloodhound, &c.” The domestic feline was afforded a similar treatment, but it seems that Webster was not so much a cat person, since he also took pains to note in his definition of this animal that “it is a deceitful animal, and when enraged, extremely spiteful.”

Watchful and Vigilant

You may already know the meaning of the words vigilant and watchful, but if you didn’t, and if you were stuck in North America in the 1820s with only a copy of John Walker’s Pronouncing Dictionary of the English Language, you would have been out of luck. That is because this book offers a single-word definition for each of these headwords, and unfortunately, they each lead back to the next (watchful is defined as vigilant, and vice versa). Granted, Walker’s book was primarily offered as a means of learning how to pronounce words, but such circularity in defining is generally avoided in dictionaries.